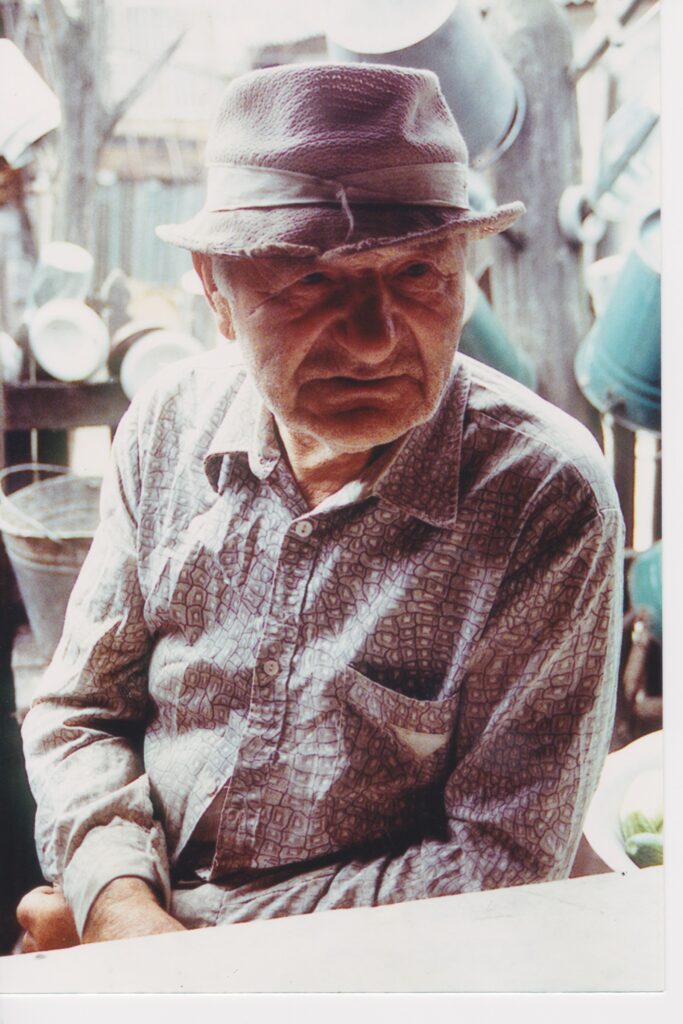

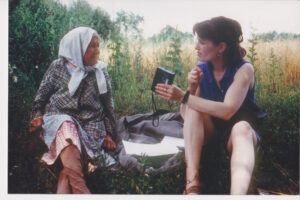

Filatov Andrii Fedorovych, b. 1909 with wife Starikova Maria Mykolaivna, b. 1914

Andrii Filatov

—Would you like to own land today?

Andrii Fedorovych: Me? I’m eighty-six; what would I do with it? Two meters would be enough for me.

—What if you were young and strong?

Andrii Fedorovych: Oh! In that case, of course.

—Would you leave the kolhosp and choose to live independently?

Andrii Fedorovych: Of course!!! I would be independent, not following anyone’s orders, planting, selling, and raising what I want. Of course, I would.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—Did you have an orchard before the kolhosp?

Andrii Fedorovych: Yes, all the land was taken up by the orchard.

—What kinds of trees did you have?

Andrii Fedorovych: Apple and pear trees.

—Did you sell the fruit?

Andrii Fedorovych: Of course. There was a famine in 1921, but our orchard gave a great harvest. We exchanged the fruit for so much grain, we didn’t know what to do with it. Stalin then started taxing orchards, so people started cutting them down.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—Were there any kurkuli in your village?

Andrii Fedorovych: What kurkuli are you talking about? We had some people who had a cart, a thresher; they were not dispossessed. Some people arranged with the authorities and bought a house in Kharkiv. The authorities said to them, “Teach someone how to work to replace you, and we’ll let you go. We’ll give you a certificate.” He took some guy as an apprentice and showed him how to work.

—We now say “kurkul” and what word did people use back then?

Andrii Fedorovych: “Kulak.” We didn’t have any well-off people in our village.

—Were there any kulaky before the kolhosp?

Andrii Fedorovych: Well, I told you that there were people who were a bit better off.

—Did people call them a “kulak”?

Andrii Fedorovych: Back in the day? No.

—Was such a person called rich or “khaziaiin”?

Andrii Fedorovych: Well, khaziaiin. For instance, when it was time to vote for a starosta, he didn’t get paid for this role. He got half a desiatyna of the land in the meadow and half a desiatyna of arable land and he worked. He had a seal in his pocket. A scribe (who held a paid position) would come to a statrosta with the documents that had to be signed or sealed. He would do this and say, “I’ll be over there in the field—plowing, or sowing, or mowing.” He worked—unlike the ones now that just walk around. If it was necessary to be on duty, we would take turns. I would be on duty today, you—tomorrow. “If the person on duty needs me, I’ll be over there.” This is how it was.

…………………………………………..…..……………..…

—Were you in a SOZ?

Andrii Fedorovych: Of course, where else could I be?

—Did you join it?

Andrii Fedorovych: Yes. They were forcing us; they didn’t let us sleep. They would summon me five times during the night, “Sign here.” First, they summoned me to a SOZ and later to the kolhosp.

—Why did they summon you at night?

Andrii Fedorovych: Because the people didn’t want to join, so they would not let them go to bed.

—Was the staff office full?

Andrii Fedorovych: Yes.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—How many Komsomol members were there in your village?

Andrii Fedorovych: About twenty.

—What about communists?

Andrii Fedorovych: Communists also numbered about twenty.

—Did the peasants want to join Komsomol?

Andrii Fedorovych: Of course. First, they were accepting only the poor ones, but later on anyone could join. If they put in an application, they would be accepted.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—What did you do in the kolhosp?

Andrii Fedorovych: I worked in the field. Some took care of the horses, some worked in the field, and others looked after the cattle; people were assigned to different roles.

—What did you get for your work?

Andrii Fedorovych: At first we received nothing, and later on we stopped receiving anything, if you know what I mean. When we threshed the first crop of grain, we were given five hundred grams; then they recalculated and took three hundred grams away and left us only two hundred grams. That’s it.

……………………………………………………………………………………….

—How did you buy the clothes?

Andrii Fedorovych: People did what they could: some had a cow or a pig; some would get paid or steal something.

—Could one steal from the kolhosp?

Andrii Fedorovych: Some could, I guess.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov and Maria Mykolaivna Starikova (Kharkiv region)

—When was the church closed down in your village?

Andrii Fedorovych: Most likely in 1930. It was a wooden church and it was burned down.

—Who burned it?

Andrii Fedorovych: A heavy tax was imposed on it, and the secretary himself burned it down.

—Is that how they said it happened?

Andrii Fedorovych: No, I knew this myself. I knew they were going to burn it down.

—Did the secretary tell you about this?

Andrii Fedorovych: Well, we were playing cards. Everyone used to gather to play cards back in the day, and he said, “I’ll burn the church soon.” I said, “Why?” He said, “There’s no way we can pay the tax.” And then it was set on fire.

—In the morning or at night?

Andrii Fedorovych: It burned down to the ground.

—What happened to the icons and the bells?

Andrii Fedorovych: Everything burned down, and the bells melted and fell down from the belfry.

—Were the people sorry?

Andrii Fedorovych: No one said anything. This is how it was at the time.

— Maria Mykolaivna, what about your village?

Maria Mykolaivna: Our church was dismantled as well.

—When?

Maria Mykolaivna: The same year [1930—Trans.].

—Did the locals do it?

Maria Mykolaivna: Yes, the locals dismantled it and removed the bells and the icons. They took the objects from the church to their houses.

—Did the people rebuild a church or sell the objects?

Maria Mykolaivna: No, it was made of brick. Even the foundation was looted.

—Did the party members plunder?

Maria Mykolaivna: Who knows.

Andrii Fedorovych: Right. Who knows?

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov and Maria Mykolaiivna Starikova (Kharkiv region)

—What was the name of the corner where people put the icons?

Andrii Fedorovych: The holy corner.

—[addressed to Maria Mykolaiivna: How was it called in your house?]

Maria Mykolaiivna: Back in the day, when people built a house, they would not start living in it until it was blessed. A priest was called to bless the house. Then they would move in and live in it.

—What was the name of the shelf where the icons were placed?

Andrii Fedorovych: Bozhnychka.

Maria Mykolaiivna: We called it vuholnychok.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—When you wanted to choose a girl you liked, did you go to the vechornytsi?

Andrii Fedorovych: Yes. A guy would go to the vechornytsi when he already knew the girl. Or sometimes they would meet for the first time at the vechornytsi.

Andrii Fedorovych Filatov (Kharkiv region)

—When the early collective farms were set up, did you have a reading house in the village?

Andrii Fedorovych: Yes, in 1931 there was a club with a library. They started showing silent films.

—Who organized the club?

Andrii Fedorovych: The activists.

—Were they locals or newcomers?

Andrii Fedorovych: Activists were sent from other places, and someone local was in charge.

—Were the activists called stotysiachnyky [Hundred Thousanders]?

Andrii Fedorovych: No, just activists. They were sent from the factory.

—Did an activist [from afar] come with his family or alone?

Andrii Fedorovych: No, he came just for a season—from one to three months maximum.