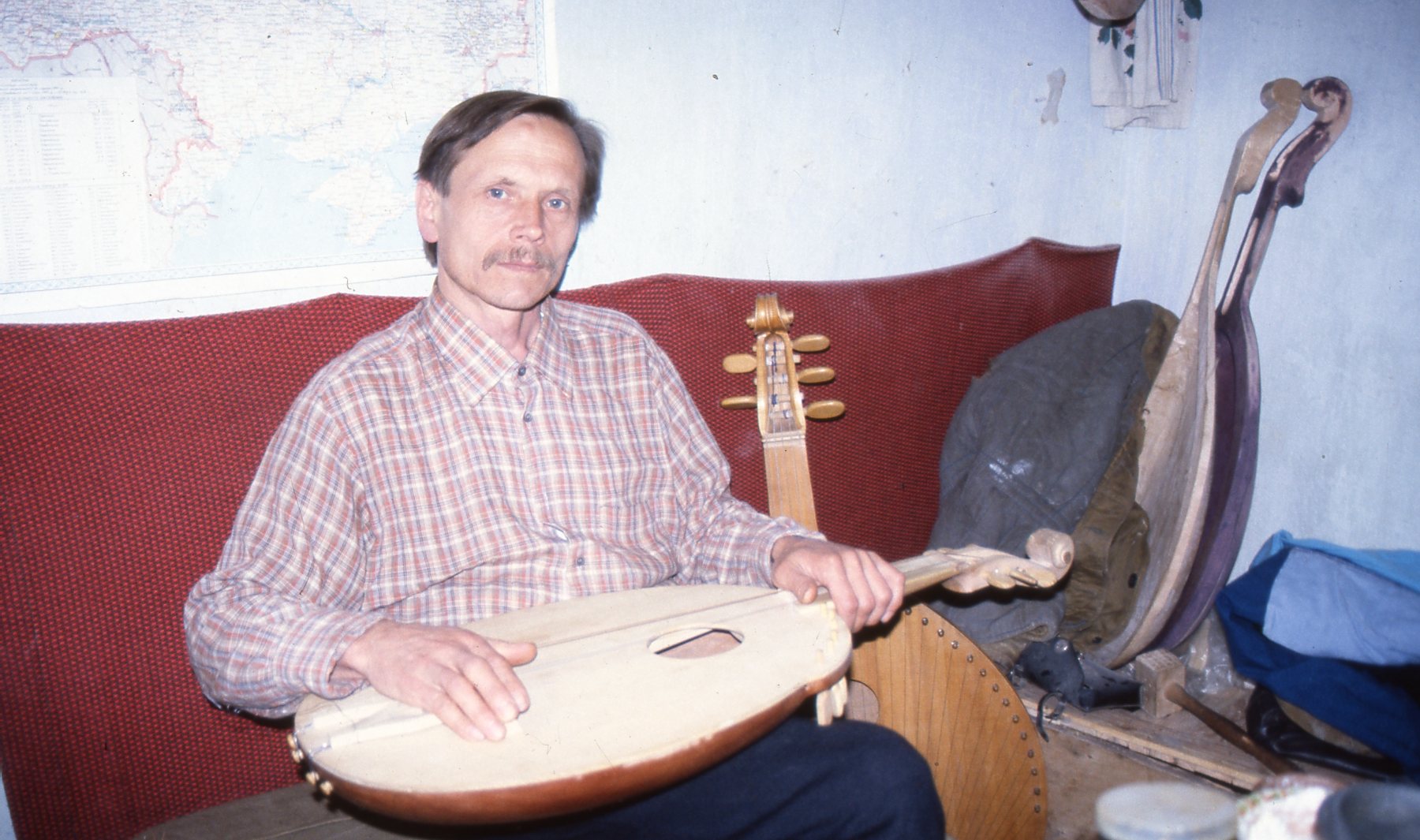

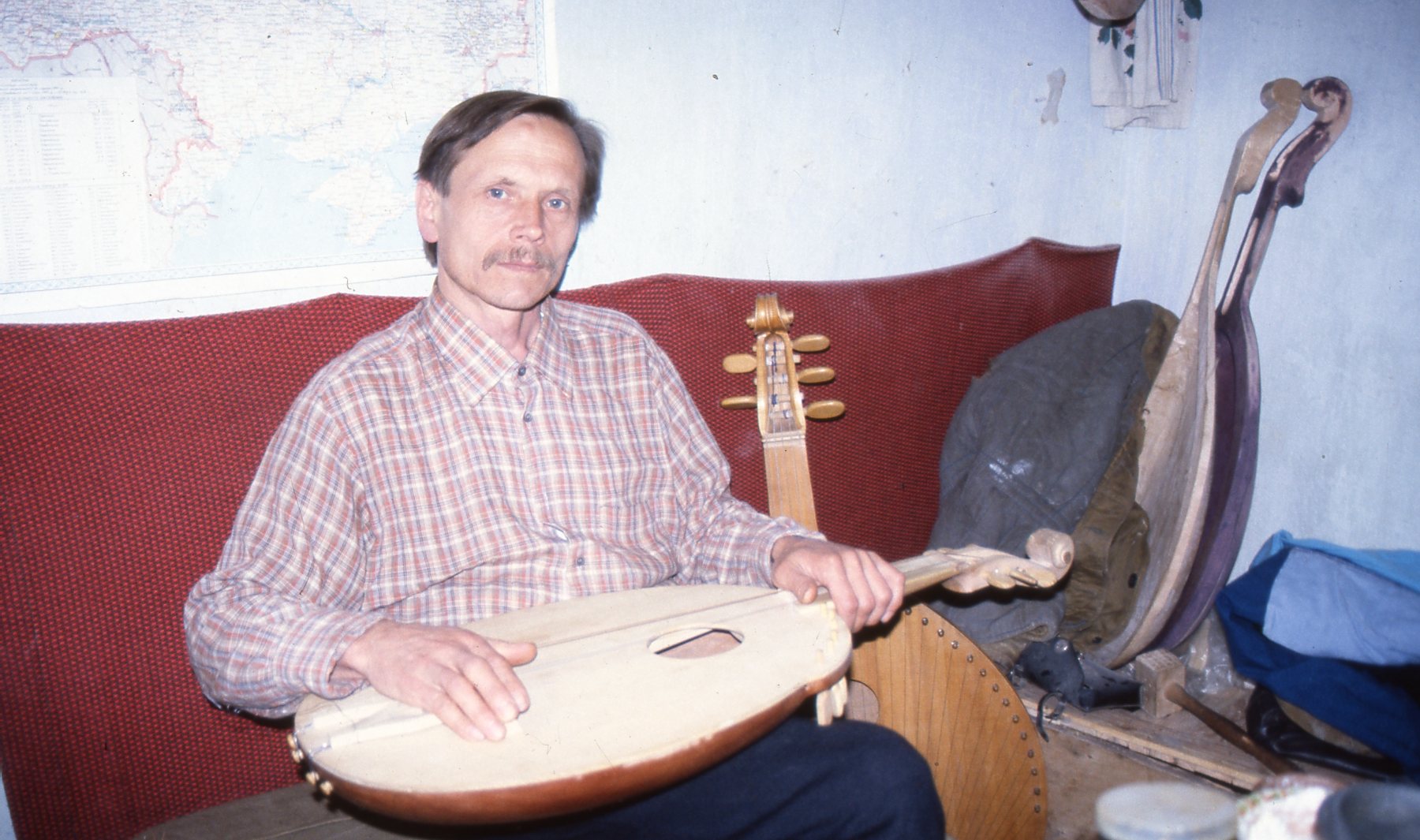

Mykola Budnyk, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Central Institute of Contemporary Art.

Mykola Budnyk, 1994. Photo from the archive of the Central Institute of Contemporary Art.

(1953–2001)

Mykola Budnyk was a kobzar, bandura player, master and restorer of Ukrainian folk instruments, artist, poet, and philosopher. He was born in the village of Skolobiv in the Zhytomyr region and died in Irpin.

He began studying the kobza with Heorhii Tkachenko in 1980. Later that decade, he founded a school to revive the old kobzar and lirnyk traditions, first in the Pechersk district of Kyiv and later in Irpin on the corner of Revoliutsiia Lane, which is now called Mykola Budnyk Lane.

He founded and led the Kyiv Kobzar Workshop where he promoted the traditional art of the kobzar. He initiated a revival of the old forms of kobzar performance (on the street, near churches, in crowded places) and the reconstruction and introduction into contemporary kobzar-lirnyk practice of diatonic Ukrainian instruments, namely, the Veresai kobza, bandura, torban, and hurdy-gurdy. He came up with a type of vertical play on the husli (in the zither family). He cultivated the Kharkiv style of bandura play, a traditional Kobzar way of singing. In addition to dumas, psalms and chants, and other Ukrainian folk songs, he brought back the melodious performance of mythological stories.

Eduard Drach, Oleksii Kabanov, Taras Kompanichenko, Oles Sanin, Taras Sylenko, Kost Cheremsky, and Yarema Shevchuk were among Budnyk-the-craftsman’s students. As an artist, Budnyk worked primarily in watercolor. He first studied drawing with Heorhii Tkachenko himself, who was known for his subtle, filigree watercolors. He later worked with his older pal, the innovative postmodern artist Mykola Trehub (1943–1984).

According to Budnyk’s student Kateryna Mishchenko, “If you consider/recall the non-iconographic, the human side of Mykola, then in my view, he was a great Player first and foremost. The word actor, would perhaps be more appropriate, but it’s tainted by a degree of insincerity in this context. No! Mykola was sincere in his game—playing the bandura, with other people, with life and death. He loved to play and often crossed the line of human understanding in different situations. People became players in his game. And he played, creating various situations for himself and for us. And we changed without even noticing. Only later did we begin to realized how radical these changes were. Oles Sanin once said, ‘Meeting Mykola Budnyk was catastrophic for each of us. After talking to him, life changed radically.’ It’s true.”