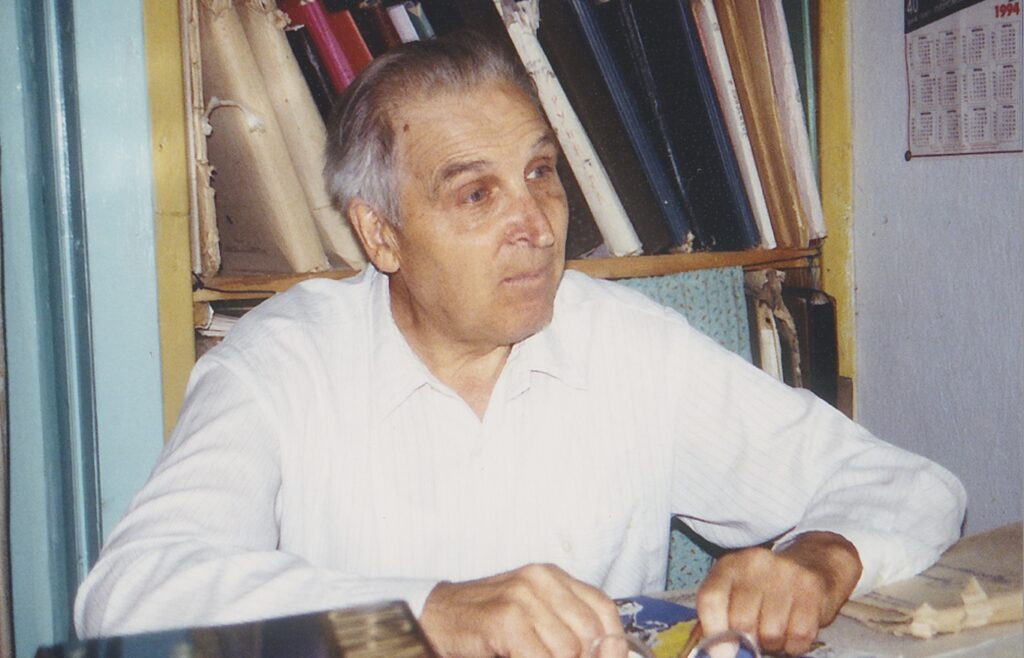

Ivanchenko Mykhailo Hryhorovych, b. 1923

—How much land did your parents have before collectivization?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Up to five hectares. They also inherited a separate vegetable garden far away in the field. My father was originally from a line of the chumaks [legendary long-distance traders who used carts harnessed by oxen—Ed.]. My great-grandfather Andrii Stepanovych Ivanchenko had twelve pairs of oxen. They were kept in a winter barn in that same garden.

…………………………………………………………………….

—Did your grandfather have a trade?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: He only worked in the farmstead. He also had a bee house in the garden, and they would put the beehives into a pit near the house (trymnyk). The round beehives were made from one log (dublianky).

…………………………………………………………………….

—Was there a garden near the house?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Naturally, there was one near the house, and there was also a separate one. The chumaks used to settle on our circular street; they would set up their dwellings in a round shape, similar to the one they set up in the steppes during the night. This is why the street is circular. It’s called Ivanchenkivsky corner.

—How was the farmstead managed before collectivization?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: I remember this. My father used to take me into the field with him when I was five, and his field was behind this garden. He would plow the field while I watched the ox. I was in a cart, and he used the horses to plow. I remember that we also had a cart, and my mother and I would go into the field on our own. I also remember how we used to go to the market; we had good horses. My father had a millet huller. The millet huller was powered by the horses. All of this was taken into the kolhosp.

—Did people come to your father’s homestead to use the equipment?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Yes, he would charge a certain measure of grain (mirchuk) as was common at the time. I remember there were twelve windmills in the village.

—Was there one owner or several?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Each windmill had one owner. I remember this activity very well. My friend Petro Karpenko and his father were millers, and I used to spend time at their mill quite a lot. The third floor of the mill was particularly interesting: it would hoot and shake as if it were a ship.

—What did your parents sell at the market?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Bread grains, piglets, and everything that the whole village was producing. They would buy various clothes; often, they would have clothes ordered and sewn in the village. There was also a carousel at the market and the smithies. As soon as you enter the outskirts of Zvenihorodka, every corner has a smithy. People could fix a wheel or a tire.

—Where were the markets set up at the time?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: In villages: Katerynopil, Talne, Zvenyhorodka—those were all our markets.

—Were there specific market days?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: I don’t remember exactly. I think Friday was market day. The fall markets, in particular, were very crowded and bustling. There were booths and tents, and people would come from different towns. This was during NEP and private trade.

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: We had some families who were deported. My father was smart, and he knew that this would happen, so he donated his property to the kolhosp in advance. If he hadn’t, he could have been deported. He had a thresher that used horses for transportation and a nice black horse; he gave them to the kolhsop. Then in 1932 the situation was uncertain. He didn’t want to join the kolhosp. The kolhosp was not set up yet, so they would herd all the cattle into a poor man’s (nezamozhnyk) barn to feed, but that man didn’t have feed for the cattle. The cattle started bellowing, and the women who were sorry for the cattle went there and took the animals home one by one. There was a crowd. In the same way, the horses were taken back to the households. Then the authorities came and took the cattle back. This kolhosp was poor. It only had thirty harrows and a few plows. They didn’t have a material base to set up a kolhosp, but they took the best fields. Now the people own the land near the school; the kolhosp has the best lands. At that time, they started setting it up.

—In what year was it set up?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: We had a co-operative to work the land (they were called SOZ at the time). It started in 1922 and was mostly made up of the nezamozhnyky [the poor], but they knew they didn’t even have the tools to work the land. In 1929, the kolhosp was set up officially during the so-called “full-on” collectivization. All the people had to join and submit applications. People didn’t want to and didn’t write those applications.

…………………………………………..…..……………..…

—What was it like when the dispossession brigade came to your father’s?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: I was at school. This was in April 1938. Two militiamen came and took twelve people to the village council. The group that went to people’s houses had two militiamen, the head of the village council, and an executive. My parents were told that there would be an investigation. My mother felt that something bad was about to happen, but my father said that it was okay and would turn out well. The authorities most likely saw the war coming and they knew that a particular category of people could turn against the Soviet regime. This is my impression because most of the people [in the brigade] were military people. My father was arrested, but we kept his notebook—he liked to write down his village philosophy on how life could be improved for the people. There was a shelf in the house close to the tie beam where he used to put a loaf of bread. In a crevice near the shelf I found his notebook; I no longer have it. They were arrested and taken to Zvenyhorodka. There was a long break in school, and our school was outside the village. They were transported by vehicles, sitting there on their knees with two NKVD representatives sitting there with rifles. My father recognized me and waved his hat at me. I have a document; I’m a member of the Society of the Repressed Ukrainian Political Prisoners. My father was arrested on 21 April 1938. On April 22, he received a negative record (kharakterystyka). He was accused according to Article 5410, and the document has his words, “I plead guilty to membership in a Ukrainian nationalist insurgent organization in Husakovo of Zvenyhorodsky regional administrative center and to anti-revolutionary work.” This is how they wrote it down. The decree of April 25 sentenced all twenty-six of them to execution by firing squad. “The Decree of the Ukrainian NKVD troika in Kyiv region of 25 April 1938. Protocol No. 228 for the accused Ivanchenko Hryhorii Dmytrovych born in 1881. Executed on 19 May 1938.” And so it was. I recently learned about how and when this happened. My mother was waiting for him all that time, thinking that he was still alive.

Mykhailo Ivanchenko:

—Did locals conduct the dispossessions?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Locals, from Zvenyhorodka.

—Why do you think they were so cruel?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Apparently because they obeyed orders. They thought that

this was the power of the poor and the proletariat, of their government and that

they had the right, as they say, to establish a dyktat [here meaning “dictatorship”].

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

—Did locals conduct the dispossessions?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Locals, from Zvenyhorodka.

—Why do you think they were so cruel?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Apparently because they obeyed orders. They thought that this was the power of the poor and the proletariat, their government and that they had the right, as they say, to establish the dictate. They obeyed their leaders because they were the party members, and the party was dictatorial. The regional committee would order, and the local party members would execute their orders. Some of them had died. One of them was the person who transported the bodies and buried some people alive. There’s one man here who’s five years older than me. He was taken to the burial place but came back to life when they paused for lunch. This is tragedy. And the one who loaded the bodies on the cart ate some bread and had twisted bowel obstruction; he died, too. The people from the Komnezam and Komsomol didn’t have much either. They were as poor as we were. They got some ration packs from the kolhosp, of course, but not much.

*That one exception is Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko of the Cherkasy region, who was arrested after the war for publishing poems in DP journals. After his release in 1954, he held numerous jobs, and was fired twelve times. He was trained as a commercial artist, and at one time worked in a sugar factory as their commercial artist. After being repeatedly fired, he decided to work on his own. He began writing and publishing books and poetry. He was eclectic in his reading habits and was widely read and was considered by locals to be a village intellectual. In other words, he was exposed to terms that rank and file villagers were not. He passed away in 2015. He told the author that during the famine “…people became stupefied—how can I put it?—psychologically traumatized, to some extent, by the famine.”

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

—Did much change when the kolhospy were introduced and your father came back?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: He came back because we asked him to. I wrote a letter because I was alone. There were cases of cannibalism in the village. I went to school, and we used to make a fire and boil snails in school. Children would die during the lessons. My mother was swollen and bedridden. One of my sisters was already dead, and the other was next to my mother. In the spring of 1933, my mother was unable to walk. Then they started gathering us at the village square. We, the children that survived, were gathered into the house of a man who had been previously dispossessed and deported and we were fed some lentil soup. A great many children died. My father came back and became the chief horse keeper. On his way back, he got out at Tsvitkovo station to drink some hot water, and the train left for Khrestynivka with his luggage and the bread and lard in it, so he came home empty-handed. I was a schoolboy at the time and cried a great deal when he told me that he had Franko’s fairy tales [Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko, 1856−1916] in that lost luggage. As the chief horse keeper, he had authority in the village, but the horses were dying just like the people. You understand? So that the horses wouldn’t fall, people use to suspend them. We started eating horse meat. My father started bringing it home along with garlic sausage; we had garlic. I still remember the smell of horse sweat. Those horses saved our lives. The Kazakhs ride a horse for about twenty km in order to make it sweat. That is when the meat is good. We didn’t know this, but we were saved nonetheless. Then people became stupefied—how can I put it? They were psychologically traumatized, to some extent, by the famine. Our seed supply was taken away and people were doomed to starvation. I remember how they searched the house and confiscated the produce. They would poke holes in the ovens and the walls with a stake. They took our bag of beans. My mother walked around crying, and the people were stunned. Then they calmed down in the kolhosp. The school started sending us to harvest kuzka [Taraxacum kok-saghyz, commonly known as the Kazakh dandelion and used to produce rubber] in the beet fields in the spring. If you harvested a bottle of it, you’d get a candy as an encouragement. People started getting back on their feet. When the grain ripened in 1933, people would pick the wheat ears. One woman was sent to prison for five years for doing so, and she never came back.

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

—How did the popular government function in the village during the Soviet regime?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: The Soviet authorities consisted of Komnezamy, the Committee of the Poor Peasants. They were the people who had formerly come from poverty [before collectivization], some were drunks that did not have a farmstead. They were given authority by the Soviet government, but the community [hromada] was held together by its own laws and its morals, you understand? The community. For example, a road had to be fixed. The community would gather for a skhodka and make decisions. The official Soviet government and the village, community government from the old times existed side by side. The community was an important player. Everyone had the right to vote, and all the community issues were resolved during the community gatherings that didn’t have any Soviet tendencies. This is how it seems to me, how I remember it.

—Whom did the village community elect?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: The head of the village council, but he was elected by the Soviet government. The community was a big influence even in his case; even the Komnezam leaders considered to some extent what the community was saying. There was no dictatorship yet.

—So, the village council and the community continued working side by side?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Yes, the community still existed spontaneously. It was in people’s hearts and people paid attention to its decisions. If it was about doing some kind of common, community work, people would discuss it during the gatherings. This was before the kolhosp, you know; people owned the land individually and worked on their land. For example, if someone’s house burned down, the community decided to help that person. My grandfather’s house burned down before the Revolution. The people had previously collected the materials to build a priest’s house but gave it to us, so we could build our house. I should say that he paid for it because he was rich, but the community had the final say. It would also make decisions about the lynch law regarding horse thieves after the Revolution. I remember there were two drunks in the village before the war, and now we have thirty-two.

—Who elected the representatives of the Soviet government?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: They were not necessarily elected—no rank, no position, no higher authority; they just had the right to vote. We had two brothers by the name of Holoveshko here in the village. People would listen to their opinion; they were the elders. The Komnezamy used to listen to them because the elders had the authority, not these newly appointed folks—even though they were the representatives of the official government and they executed the orders imposed from those above them. Nonetheless, they listened to the older people; such was the custom. If something happened, the community would decide whether to let someone new live in the village or if someone wanted to get married.

………………………………………………………………………………………..

—How did people treat the Kolsomoltsi?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: They were laughed at, especially in 1932. There were many humorous anti-Soviet and anti-kolhosp songs. The village itself did not accept them, but there was pressure from the government. They would give us a good deal of Soviet propaganda in school, but we understood it very well because our parents laughed at it all. Collective farming does not give the same results as when you own the land.

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

—Were there painters-bohomazy?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Painters-bohomazy? Yes, I’ve heard of them. More often, those were professional painters. For example, during the difficult 1920s, there was a painter Diachenko, a relative of Shevchenko. He died of hunger in Kyrylivka. He painted icons. There was also Makushenko in Lysianka. He studied in the Academy of the Arts and painted icons. There were more bohomazy whose names I have forgotten. There was one in Stepne. I have notes on their names somewhere. When I came back from the concentration camp in the Far North, I no longer painted; just made a couple of icons. The village people asked me to.

—Did the people bring you the reproductions?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: No, no. I had my own. I started working in Talne. First, they didn’t want to give me work, but later accepted me into the dom kultury [Building of Culture]. I was allowed to live one hundred km away from Kyiv. One photographer in Talne started taking photos of the icons. At the time, I was making oklad, the shiny gold plating. I was cutting out the flowers for it. This was our enterprise with the photographer until I was called by the authorities and told to stop doing it.

—Who called you?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: The authorities in the Department of Culture. The KGB established strict surveillance on me—both disclosed and undercover surveillance. I also had so-called ‘friends.’ They did their job well, but I knew what was going on. I had intuition. I had seen everything in the concentration camp.

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

—Do you remember how the club was set up in your village?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Yes, the club was called the village house at the time. It used to be the priest Pidhursky’s house. His house was about twenty meters farther down than the current club. I remember how the old staff of Prosvita staged performances in school. When I was still too young to go to school, they would take me to these shows. I don’t remember the story, but I remember the stage, the artists, and the swords. The amateur theater was very good. It was made up of haymakers who would make hay barefoot in the summer and then come to rehearsals in the club wearing their linen work pants, barefoot. Everything I know about the classical plays—and, in essence, our Ukrainian mentality—is from our village and those performances. Let me tell you what went on there. We were schoolboys, and under the stage there was a plank that could be removed. The three Bondarenko brothers and I would get in through that opening when the guard wasn’t there, and we’d wait. The audience would come A prompter would light up a candle in his booth. Then we’d come out and find a seat in the hall. The fiddle would start playing. They were mostly trios. People didn’t chase us away, so we the young schoolchildren watched those performances. All the classics—and not in some large theater, but in Husakove. The shows had a big impact on me, on the development of my personality. You understand? I don’t mean just a national feeling, but my spiritual world. Major excitement.

—Who went to these shows?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Absolutely everyone. A ticket cost five or ten kopeks. It was a full house, and some people stood in the hallway. The hall was small. People took a great interest in this and respected the artists.

—Was Prosvita popular?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: This was their work. We had a teacher named Kateryna Safonivna. She was a long-time member of Prosvita, and so was her husband. They were all educated there. The same goes for the choir members. We had a very strong choir singing culture. When Prosvita was banned before the Revolution, their choir merged with the church choir. People gathered for small parties. In the garden that belonged to my parents, the kolhosp set up a bee garden, and Yosyp Yosypovych was its guard. He was such a romantic person. He was a good singer and wrote poems—simple poems, of course. He was also very strong physically.

…………………………………………………………………………………

—Were there any fiddle players in the club?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Yes. There was also a large double-bass in the club. We would be sitting under the stage, and the fiddles would start tuning in. Then they would turn the lights down. We had kerosene lamps and the stage was small.

—Did bandura players come to the concerts?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: Outsiders didn’t come, but locals did play. Filimon Oksemenko and Faust Seredenko were the local men who played the Cossack dumy and the classics. This was in our village. Faust Yosypovych Seredenko was a teacher, and the other one was just a Prosvita member. He organized Prosvita activities here during the German occupation, too. When the Germans were leaving, they took him. Seredenko was the choirmaster during the German occupation. The girls from the tenth grade sang Ukraina. No one reported on him, but I must say he moved to another village. He could have been sentenced to ten years. Mykola Panteleimonovych Sokyrko whom you interviewed earlier was sentenced to ten years for his work with Prosvita because he was also a choirmaster there. Petro Muzyka was in charge of Prosvita, and he was sentenced to ten years.

—Did he get his ten-year sentence because he was a leader of Prosvita?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: He sang Ukraina. It was considered anti-Soviet behavior at the time.

—When did he sing it?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: In the fall of 1941. A group of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) was being organized here. They were about two hundred people going to Poltava. They stopped in Zvenyhorodka and started organizing a network of OUN here as well as starting Prosvita groups. Hryhorii Syvokin was the regional leader here. He was executed by a German firing squad. Mykhailo Omelchenko was the district leader. They were locals. Only one was from Halychyna [Galicia], but he wasn’t arrested. He managed to flee. I remember how the Prosvita office was opened in Husakove. There were two halls in school separated by a wooden wall. One could remove it and have a large hall with a small stage. The representatives were sitting on the stage. There was a portrait of [Taras] Shevchenko that a teacher painted with my paints and printed portraits of [Symon] Petliura and [Stepan] Bandera [OUN leader] on either side of it. Mykhailo Omelchenko was the district leader of the OUN, Hryhorii Syvokin was the regional leader, and Artem Tkachenko was another one. He was in prison in Solovky, but he ran away from there. Tkachenko recited a duma about the Solovky seagull from the stage, with feeling, and some men cried, you understand? Then he read the poems by Melaniuk. I remember this because this was how I learned about him. At the time, [Volodymyr] Sosiura wrote a letter to Melaniuk. The Germans allowed them to develop, like film negatives, and then they started arresting them in the spring of 1942. Artem Tkachenko resisted and killed a policeman. I saw Syvokin—he was all beat-up. He was not tall and had fair hair. He was shot in Kyiv because he had connections with the Kyiv office. Their representatives were beaten in Uman, and Yurko Omelchenko, the son of Mykhailo Omelchenko, disappeared. Yurko completed four years of university and ran away. Postolenko, who worked in the editorial department, only lost his teeth in the fight. He wasn’t shot because he had only worked here for one week. They let him go. Both of them were in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) later on. Postolenko came back and was sentenced to twenty-five years. He served his sentence in Vorkuta. Yurko was somewhere there, too, and he died. These guys organized Prosvita in our village.

Mykhailo Hryhorovych Ivanchenko (Cherkasy region)

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: People in the village have always sung songs, even after the famine of 1933. When people were walking home from the village hall after a play or a film screening, each street would carry a song along. Folks from one street would sing one song. The other street would sing another one, and so on. The whole village sang. Then they would stop somewhere at the pasture, at the crossroads, for half an hour because they had to go to work the next day. Each street had its so-called lead singers. Right now, we don’t have this tradition because the young people don’t know how to sing. They know absolutely no folk songs. The songs were very sad and jolly, but very long also, picturesque, vivid. They would recreate images, the state of mind, the landscape, and the people—those were very nice songs.

—Did the girls still sing the spring songs?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: They used to go to vesnianky. These are spring songs. Later they sang songs for Kupala Night and St. Peter’s Day. When I was a shepherd, we also had folk games. We don’t have them any longer. For example, there was one called “the baker” where they would put a stick and you had to knock it off. We had all kinds of games.

—Did the girls do a zigzag dance [kryvyi tanets] in the spring?

Mykhailo Hryhorovych: A zigzag dance? I remember something like this; it was before the war.