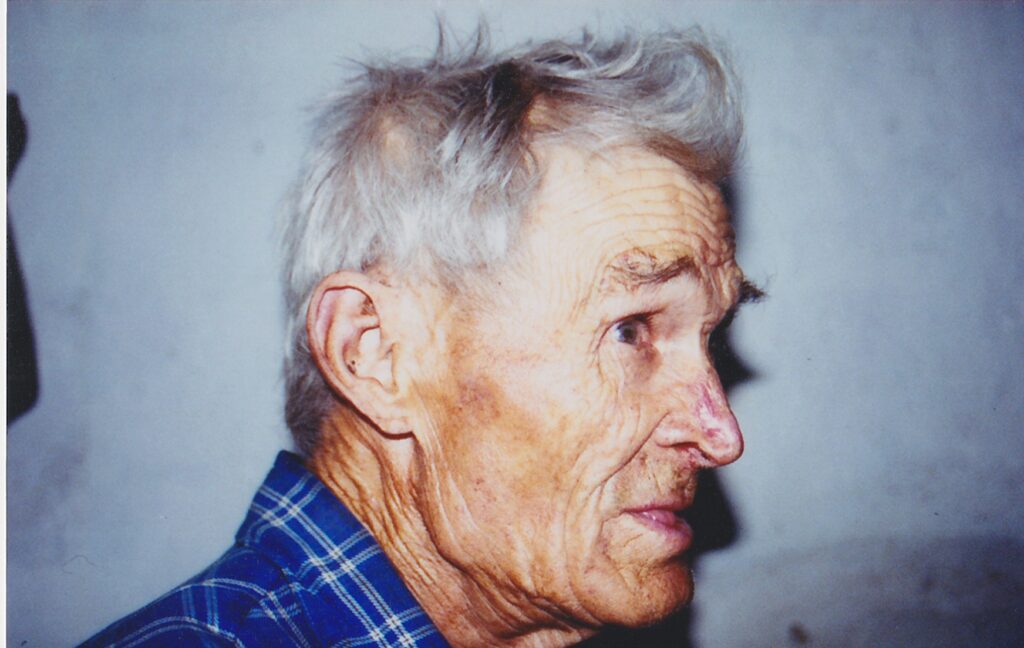

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko, b. 1919

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko (Cherkasy region)

—How much land did your father have?

Ivan Kalistratovych: One and a half hectares and then he got some more on the hill, so he became a seredniak. Then they confiscated our grain, and we were swelling from famine.

—How many head of cattle did you have?

Ivan Kalistratovych: A horse and a cow. With the amount of land that we owned, we were not allowed to have more cattle. If one had five or six hectares, they could get more animals. And if you only had 1.5 hectares, what could you do? You had to plant potatoes. Now we can buy food in the stores, but back in the day you ate what you produced; you couldn’t get it anywhere else. You could buy it on the market, but money was hard to make. My father used to weave on a wooden loom; even I used to weave, too.

—Did your father weave for the family or for other people as well?

Ivan Kalistratovych: He took commissions. I think he’d make three arshins for the people and the fourth one for himself.

—What exactly did people order?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Thin threads (desiatky and trynadtsiatky), coarse woolen cloths (riadno) and rushnyky. He also made shoes and worked with an ax; he made windows. If he didn’t have the energy, work was not done. Mostly he made things for the family.

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko (Cherkasy region)

—Describe the beginning of the kolhosp.

Ivan Kalistratovych: It was simple. In 1929, they announced, “Everyone must join the kolhosp!” Whether you wanted or not, you submitted a notice and joined the kolhosp; they took away your horse and cow. We had a small barn with long shelves inside: “We’ll take these shelves.” To prevent the barn from falling apart, my father then put up two thin poles; they came and destroyed it. Everyone was forced into the kolhosp, and then later on they declared freedom: those who wanted could leave the kolhosp. Some left and then joined again; back and forth this went. Then we settled down. Those who left the kolhosp didn’t get their land or cattle back—nothing. Those who protested a bit were evicted and deported right away—right away.

—What did people think of those who were exiled?

Ivan Kalistratovych: No one could think or say anything because everyone

lived in fear. Today one was arrested; I could be next. No one could know

or think anything. In 1947, there was [Marshal Kliment] Voroshilov’s Decree to exile mostly the people of Western Ukraine because they did not obey. In our village,

we also had meetings. Those people were called “unreliable” and “accomplices.”

Everyone was lying in the grass and thinking, “Would it that I was not named.”

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko (Cherkasy region)

—How many families were exiled?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Seventeen to eighteen. None of them came back. They must have been executed, as I’m hearing recently. People say they were executed on the way.

—What did people think of those who were exiled?

Ivan Kalistratovych: No one could think or say anything because everyone lived in fear. Today one was arrested; I could be next. No one could know or think anything. In 1947, there was Voroshilov’s Decree to exile mostly the people of Western Ukraine because they did not obey. In our village, we also had meetings; those people were called “unreliable” and “accomplices.” Everyone was lying in the grass and thinking, “Would it that I was not named.”

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko (Cherkasy region)

—When was the club built?

Ivan Kalistratovych: The old club was in the priest’s house after the 1920s.

—Was the church completely destroyed?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Yes, it was wooden, so if someone had looked after it, it could have been still here. It’s a pity they want to destroy the other one in the volost′too, but the villagers are protesting there. They had Slupitsky in the village council, such a mean person. The village council would take apart the schools if they needed a piece of roof. Such thieves they are.

—What kind of volost was this?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Similar to the village council. They joined some villages to it. There was a landowner’s enterprise—your average agricultural technician. He worked for Pototsky. He was considered a landowner, but he didn’t have much land.

—Did they show films in the priest’s house?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Movies and plays. It was a good time. There was no library back then.

—Was there Prosvita in your village?

Ivan Kalistratovych: If there was no library, there was no Prosvita. When the library was organized, they also started setting up drama, singing, and music groups.

—When was this?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Starting with NEP. After collectivization, we had a famine and everything went downhill.

Ivan Kalistratovych Udovychenko (Cherkasy region)

—Four men or four bandury? I don’t think I understand.

Ivan Kalistratovych: Faust Yosypovych Seredenko was a village teacher who played the bandura. He liked to sing and play chess. He had a bandura and he probably still has it. We would make our own instruments. I played the mandolin and used to accompany others on the guitar. I wanted to have a bandura, so we found a wide enough pear tree in the old gardens, and the kolhosp gave us permission to cut it. We cut it into four, and the four of us started making bandura. Filimon Oksemenko played, too. The bandura didn’t turn out well. When the wood got dry, it cracked. I, however, treated the wood in hot water, got its juice out, and then carved it little by little. That was the secret. You can’t tell the width of the instrument’s wall right away; it becomes apparent in the process as you carve, you feel it with your fingers from the bottom. I followed the drawing when I was making it, but it didn’t turn out the same way.

—Where did you see the drawing?

Ivan Kalistratovych: In the newspaper. Mine came out a bit different, but it played. Seredenko and Oksemenko were players, too. I only learned one duma, and then the war began. Seredenko went one way. The Germans took Filimon, and he died somewhere on the way. That was the end of our story.

—What duma did you learn to play?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Shevchenko’s “My thoughts, my thoughts.”

—Why did you make the bandura out of a pear tree?

Ivan Kalistratovych: There was no other wood at hand. The pear tree is thick and sounds as good as the maple. Back in the day, people used to make spoons out of pear and maple trees. I used them as examples. A teacher from Motriivka learned that I had a bandura and paid me three hundred rubles for it. He kept it.

…………………………………………………………………………………

—Do you remember the music that was played at weddings?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Fiddle and bubon, or two or three fiddles.

—Who was the musician?

Ivan Kalistratovych: Ivan Dikhtiar, my uncle. He was also repressed and never came back. Every Sunday, there was music and singing in his backyard. It was fun.

—Why was he repressed?

Ivan Kalistratovych: His brother and he were repressed. He was a peasant. We didn’t have any professional musicians, just amateurs.

—Did he have an ensemble?

Ivan Kalistratovych: He just played. There was one man who made a double bass. He even lived in America. He came back here without any documents. He got here on a prison transport and walked three years to get here. He made a wooden bicycle; we didn’t have any at the time. He would be riding his bicycle, and a crowd of men would follow him. Then he made the double bass. Someone else had a bubon, so that was the music we had in the village. Today, it seems like everyone is doing well, but I feel morally stifled. No one wants to sing, no matter what. Back in the day, two or three people would get together: one small balalaika, and there you go—you had a dance. People would come barefoot, wearing their linen skirts.