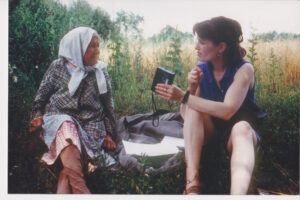

Maria Petrivna Voitenkova (Kharkiv region)

—How much land did your parents own?

Maryna Petrivna: You see, my parents were landowner’s serfs, so they didn’t own land. After serfdom was abolished, the village was named Popivka. My mother was not yet married to my father, and my father’s parents were serfs.

—Do you remember the name of the landowner?

Maryna Petrivna: No.

—Was he a Pole or a Ukrainian?

Maryna Petrivna: I don’t know; I had not been born yet. After serfdom was abolished, my grandfather went to work everywhere. He used to go far away to do various jobs to earn money for his children. I think he went as far as Tomsk, but I’m not sure. This was before I was born.

—What did your father do?

Maryna Petrivna: My father started buying land in Lytvynivka. Then the children—my siblings—started earning money because they were poor. Where they worked, they were paid nothing. After they started buying land, we started keeping cows. I used to graze the cows and we would get chased away from there; they didn’t let us be.

—Who was chasing you away?

Maryna Petrivna: The local shepherds said, “Graze your cattle in Popivka.” I wasn’t chased away when I grazed cows, but my brothers were. We had two cows and some calves.

—Did you have a garden here?

Maryna Petrivna: My three brothers settled here. They used to be serfs and then moved here. At the time, you’d save some money and buy three-quarters of a hectare. People used to get three-quarters of a hectare of land if a boy was born, but our brothers didn’t get the land because they were serfs. So, they saved money and would buy land if someone was selling. This is how we got a plot of land in the field.

—Where did they get the money to buy land?

Maryna Petrivna: My three older brothers worked for the rich people. They had an agreement to be paid with clothes and money. My father would take their earnings to buy land. He himself worked for a rich man who lived down the road. That man was later dispossessed and all of his family died. My father worked for him and would come home for the night.

—Was he a rich man?

Maryna Petrivna: Well, yes. He had a lot of land and hired workers. My father helped with the cattle. He had to make a living because he was taking his children’s money to buy land since we didn’t get any. I had three brothers; I wish we had grown to own two hectares, but it was not meant to be because my brothers were serfs.

Maria Petrivna Voitenkova (Kharkiv region)

—Was there a famine in the village?

Maria Petrivna: Yes, it happened as soon as I got married in 1921. I didn’t have children at the time, so we made it. Then in 1933 we had another famine, and people died. In our village, there weren’t so many deaths. We live close to the road to Kharkiv so we could go to Valky and get some food there. I had a cow at the time, and my husband used to bring something from Kharkiv because he worked there. This famine didn’t impact us very strongly. Both of my sisters came to my house to get some food.

Maria Petrivna Voitenkova (Kharkiv region)

—How much were you paid?

Maria Petrivna: We were not paid. This is why our pension allowance now is so low. It’s because we worked for nothing and there’s no account to draw pension funds from now, so we could have a larger allowance. We did all kinds of work: during the war, women used to dig the soil in the field with spades and stack hay. Two of them would carry half a stack using two sticks. We would walk very far into the field; the field was far, and we had to walk everywhere. As for the sugar beets, we had to dig them manually. It was hard work and you had to give the harvest to the kolhosp.

—And you never got paid for any of this work?

Maria Petrivna: Never. One time, I was given a ruble, and I lost it on the way; it fell out while I was walking home.

—Were you given any wheat?

Maria Petrivna: Yes, wheat and corn. They didn’t give us any beets. When my husband became an agronomist, we were paid with potatoes; they gave us a lot. In the beginning, there were no extra potatoes to give to workers. My husband did a good job breeding potato varieties. He would have a team of two or three women to dig out the bad potato varieties.

Maria Petrivna Voitenkova

—Were the local authorities opposed to people having icons?

Maria Petrivna: Some icons were thrown away or hidden away, some were kept. They couldn’t make people throw away everything. We didn’t throw anything away.

—Did you hide them?

Maria Petrivna: No, we did not.

—Did they come to you asking why you kept the icons?

Maria Petrivna: No, they did not come on purpose. Sometimes a guest would come and see the icons, but a guest had no right to make me throw anything away. The authorities would go around asking whether people acknowledge God or not and they would take notes. My husband and I said, “We acknowledge God.” They made a note. Some people would say, “We do not acknowledge.” They would again make a record of that.

—Was this before the war?

Maria Petrivna: Yes, before the war, when the times were turbulent.