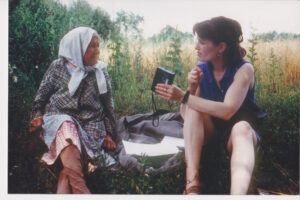

Tetiana Panasivna Saliienko (Kharkiv region)

—What is your maiden name?

Tetiana Panasivna: Andriievska. We were exiled because we were labeled kurkuli.

—What did your parents have?

Tetiana Panasivna: They had horses; there were no plowing machines at the time. We had a few cows and three horses: two in the plow and one for breeding. We would milk two cows and raise the calves. We had a pasture, and some people used to graze their cattle on our pasture.

—Did they pay you for this?

Tetiana Panasivna: We had an agreement that they would either pay with money or help us cut the hay.

—How much land did you have?

Tetiana Panasivna: My father had forty-four desiatyny.

—What did he sow?

Tetiana Panasivna: Wheat, rye (mandatory), barley, and oats. We never sowed peas. If we needed some, we would sow the yellow one, y’know, in our vegetable garden. It was better for us than the green one.

—What crops did you sow for sale?

Tetiana Panasivna: My father didn’t grow vegetables for sale, only wheat and rye. During some years, we had to sell an animal because we didn’t have enough money. This year was a drought, same as some years in the past.

—Where did your father sell the produce?

Tetiana Panasivna: There was a place in Valky and Sytky nearby opened by the man named Hruba. His wife would receive the goods, and he and his Jewish partner would load the grain and send it off somewhere else.

…………………………………………………………………….

—How many day laborers did your father hire?

Tetiana Panasivna: There was one who worked for bread and money. Later on, we had the means to buy a mower that was drawn by horses; that was a great help. We the children would run around barefoot at the time even though people said that my father was rich. He was dispossessed, but at the time you couldn’t buy shoes anywhere; people would hire a cobbler to make the shoes.

—Did a cobbler come to your house to make the shoes?

Tetiana Panasivna: No, they would look for one to hire as a live-in worker. We would feed and pay him. At the time, only the adults had their clothes made for them; the children would just wear linen shirts until they grew up. When the boys grew up, they wore pants.

—Who made the cloth?

Tetiana Panasivna: Other people. We didn’t do this because there were nine children in our family; our mother didn’t have time to weave. We would sow hemp and flax, but we didn’t know how to prepare it for weaving. Other people did.

…………………………………………………………………….

—Did your parents have an orchard?

Tetiana Panasivna: Yes.

—Was it large?

Tetiana Panasivna: It was cut. It was near a pond. It was a very good orchard. At the time, my father would sell the fruit in Vodolaha.

—The apples?

Tetiana Panasivna: Yes, apples or pears. We would also dry them. We were made to cut them, and they would dry. My father sold the dried fruit to enterprises.

—Did you have a pond?

Tetiana Panasivna: Yes, our own pond.

—What about the forest?

Tetiana Panasivna: We still have twenty-two hectares of the forest, but I cannot take any logs from there.

Tetiana Panasivna Saliienko (Kharkiv region)

Tetiana Panasivna: When I was a student, my father was renting an apartment in Valky, where we have a bus station now. At the time, we didn’t say “the university”; we said “gymnasium.” This is where I studied.

—How many years did you study there?

Tetiana Panasivna: Not long. My mother said, “Child, you need to help at home. Enough reading and writing. Help your mother.” I completed the village school and studied for three years at the gymnasium. They taught French there. There were no Ukrainian classes, and I didn’t learn it.

—What was the language of instruction in the gymnasium?

Tetiana Panasivna: Russian.

—Did your siblings go to the gymnasium?

Tetiana Panasivna: No, only I. The older ones didn’t go; our father wouldn’t let them. I was the one who asked to be sent there because I was getting good recommendations in school, so he let me study more. But you had to pay and buy your child the boots and clothes, so later on he said: “You studied a little; that’s enough. You need to work, child.” He made me work.

Tetiana Panasivna Saliienko (Kharkiv region)

—Were there any bohomazy in your village?

Tetiana Panasivna: I haven’t seen any. My parents bought ready-made icons. There was a store that sold them. When a couple was getting married, they had to have two icons for the wedding: Christ the Savior and the Mother of God. When we were chased out, I lost track of who kept the icons. Later on, I found one at my in-laws, but the icons that were for sale were expensive.

—How many icons did your parents have?

Tetiana Panasivna: They had icons in each corner; for example, that one is theirs. They didn’t have more icons than that. I have seen many more icons at some acquaintances’ houses. One woman invited me for her grandfather’s funeral, and I saw so many icons at her place. Her room was smaller than this corridor, but the icons were of all sizes. She said she used to pay four hundred rubles for each at the time.

—How many icons did you have when you started living here during the kolhosp era?

Tetiana Panasivna: Just my benediction. I gave icons to those who didn’t have them; they were learning. Her mother died long ago. [Pronoun antecedent of “her” is unclear in the original.—Trans.]

—When the kolhospy started, could you keep the icons in the house or did you have to hide them?

Tetiana Panasivna: No, I never hid them, and no one asked me about them. Not even during the German occupation. The Germans were not against icons; they even liked them. No one reproached me or threw away the icons. The foreigners were nasty in so many ways, but they didn’t throw away the icons.