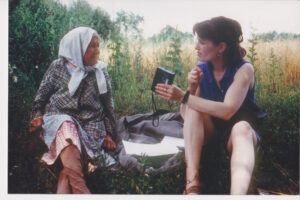

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk (Kharkiv region)

—When the Komsomol activists came, did you ask them, “What are you doing?”?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Who could say anything? I lived at my mother’s, and they came and took everything we had—canvas blankets (riadiuha) and the bags of grain. It was the time of the kolhosp, so they took everything.

—Did you go to the administration to dispute this?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No. My husband and I were building a house; we put up the walls but didn’t have a roof yet. We bought a barn. Then the famine began. We didn’t live at home at the time; my husband was away, and I used to go away, too. The kolhosp workers took the wooden planks and the rooftop. Where could you go to dispute this? Nowhere.

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk (Kharkiv region)

—When the kolhosp was set up, did you and your husband join immediately?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, we didn’t join. Some people did, and my husband was a hired worker in Mariupil, Slavenske. He also worked for various people before he got married. In 1933 after the famine, we joined the kolhosp.

—What were you told in 1929 since you didn’t join the kolhosp?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Nothing.

—Were you not forced?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, not us. Those who wanted to, joined.

—How many people in your village didn’t join the kolhosp in 1929?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: I don’t know. Many.

—About ten families or more didn’t join?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: More.

—Were you able to keep the land and the cattle or did the kolhosp take them away from you?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: We had nothing. My father-in-law owned something, but we had nothing.

—How did you make a living?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: I lived at my mother’s, and then we bought a little house here and my husband moved in. He was in Kharkiv up until the war. I was in the kolhosp and he had a cow. My husband would come back home for the weekend; I would normally take the cow to graze and he would bring it back home in the evening. One neighbor used to say to him, “You don’t work. Go to work.” It was a very hard time for us before the war; he went to Kharkiv to work and would come home for the weekend.

—Was the brigade chief angry that your husband didn’t join the kolhosp?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No one said anything, not the top administration, not anyone else.

—You said someone scolded you when you took the cow for grazing?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Back in the day, Saturday was a day off.

—Why did you join the kolhosp in 1933?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Everyone joined by then, and so did we.

—Before you joined the kolhosp, did the people tell you to join?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No one said anything.

—You just wanted to join in 1933?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Well, 1933 was the famine year. My husband was in Mariupil and came back. People died by then, but there was work to do in the field—mowing and sheaving. We both joined the kolhosp. One day, they were stacking hay and my husband fell down. He never went back to the kolhsop. He went to Kharkiv instead, and I worked in the kolhosp until I was sixty.

—When you joined the kolhosp in 1933, did this help you survive the famine?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Oh! We had already survived the famine by going around to other places to work: to Kuban, to Komaryky. Where didn’t I go? I traveled to exchange various goods so we could eat.

—You had one son during the famine?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Yes, born in 1928.

—What goods did you use to exchange?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Anything we had—the linens, the dowry.

—And in those places you went, did the people want to exchange this for produce?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Yes, anything could be exchanged.

—Did you take your necklace there?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: I didn’t have a necklace, but some people did bring one for an exchange.

—When you were coming back from Kuban, did people come out to the road and ask you for food?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, at the time we used to go there, some people would cross our path and take the food away. In 1947 my son went to Kuban (I didn’t go anymore) and he was robbed of his food on the train. They took his backpack from his back.

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk (Kharkiv region)

—Who dispossessed people?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: The locals.

—Were they from Komsomol or from the party?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Komsomol activists.

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk

—What was the name of your church?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: The Trinity.

—Where was it located?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Near the square.

—What happened to it?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: It was demolished, and the bells removed (they were made of copper). There was one person who built his house out of it; I don’t know where he is now.

—He built his house out of the wood that was used in the church?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Yes.

—Who was he?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: A communist.

—Did the village locals remove the bells?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, strangers came from somewhere, removed them, loaded them, and left.

—What was done to the icons?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: Maybe the people took them; I don’t know.

—When was this?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: In 1929, in 1930, when the kolhosp began.

—Why did they do it?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: It was in somebody’s way. In the communists’ way, who else?

—Why?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: I don’t know why they ruined it.

—Did communists go around the village telling people to remove their icons from the walls?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, they didn’t say anything about the icons, but they went around confiscating grain in 1932, taking whatever people had, checking attics. What can you say? No one said anything.

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk (Kharkiv region)

—Did the Communists go from house to house telling people to remove the icons?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, they didn’t say anything about the icons, but they went around confiscating grain in 1932. They would check everywhere and take everything. What could you say? Nobody said anything.

Anastasia Trokhymivna Kalashnyk (Kharkiv region)

What kind of music did people play at weddings?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: A harmoshka (harmonia), and troiista muzyka (“trio”):

a bas [“bass,” here about the size and shape of a violincello], a fiddle, and a larger

fiddle. There were two fiddles: a tiny one and a large one. The third one was that bas.

………………………………………….

—Was there still bas after collectivization?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: After collectivization? No way! There was nothing.

—No fiddle either?

Anastasia Trokhymivna: No, and weddings were not celebrated. There was only harmonia, [while] the people who could play [the string instruments] died during the famine.