Peasant Music Specificity

Rural music practices are (or in most locales in Poland, were) region-specific to the degree that certain dominant music forms, genres, styles, ornaments, instruments, ensembles, melodic types, etc., are peculiar and unique to a given region and are not common outside of that region. Villages only a few miles apart might have nearly completely different repertories and instrumental ensembles. Secondly, many peasant music practices are specific to a given social group. For example, most ensemble music among peasants is quite different from that of other rural dwellers such as rural nobility. Peasant musicians, in most Polish dialects known as muzykanty, are first of all agriculturalists. Their farm-derived income is primary. They usually practice music as a part-time craft to obtain a supplemental income. Next, most peasant music practices are specific to a certain time period in the sense that village fashions change through time, albeit often very slowly. Many village music practices today stem from one of various earlier periods, which through time became mixed with music practices of later periods.

Three basic kinds of music practice and performance context can be said to be most common in the Polish countryside today:

- a longstanding region-specific peasant music, derived from periods preceding peasant enfranchisement in the mid-nineteenth century, which survives only in certain regions; the performance context is primarily the peasant wedding sequence, which demands the ritual execution of specific melodies, metro-rhythmic norms, and dances;

- a largely non-regional village music that is an adaptation of the popular and widespread idioms of the last 100-150 years in the industrialized world (e.g. waltz, polka, schottisch), including radio-derived idioms of the last several decades (e.g. two-step, tango, foxtrot as well as rock and pop); the performance context is primarily social gatherings in which music of wide dissemination is realized in a non-ritual fashion;

- state-sponsored music ensembles that are characterized by culture control mechanisms exercised by both music professionals and non-musician specialists, often bureaucrats, and featuring non-regional music idioms of national appeal; the performance context is primarily the stage, concert hall, recording studio, or radio and T.V. broadcast.

In Poland and most of East Central Europe, the music changes over the last century have included the breakdown of music context specificity, the mixing of regional music practices, and the creation of numerous hybrid genres of music; especially as urban fashions have entered village life, and the wide dissemination of national economic and political institutions have made the rural dweller more conclusively than before a participant in broadly distributed cultural norms.

Peasant Music Context

The main music context for the small peasant ensemble in Poland until recently has been the ritual wedding sequence. This is true not only for Polish lands, but over most of East Central Europe as well, and to a certain extent among peasants everywhere in the world. Until recently, of all music performance contexts in the small community, the wesele (“wedding sequence”) was the most important, frequent and profitable for the village musician. This is not simply an exchange of religious wedding vows, but a several days long sequence of events in which the peasant music ensemble plays a pivotal role in most regions in most time periods in Poland. Also, the wedding sequence is the longest and most complex of all peasant ritual practices.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, other music performance contexts of lesser importance were common in villages. Today, most of these situations in most regions, where they still exist, no longer feature music. These largely past music performance contexts include: baptisms/ christenings; quasi-ritualized seasonal or social gatherings such as dożynki (“harvest festival”); religious events such as the evening before Advent or Three Kings Day; social parties (today often called zabawy, but before 1939 or so most often known as potańcówki in many regions); certain labor-related contexts such as feather plucking and potato digging; and evening dances at the village inn (karczma). The repertory and other music practices that were common to these performance contexts are not well documented for the period before the 1930’s. In all probability, the repertory at some of these occasions was not context-specific (e.g. social parties, labor-related contexts, and village inn dances), while at other occasions a repertory specific to that one context dominated. For example, at gatherings celebrating religious events, the religious melodies in some locales might or might not have been accompanied by the village instrumental ensemble as the village participants sang. For the muzykanty, this was strictly an accompanying role that earned them little if any extra income, rather usually food or goods in exchange for playing.

Formerly, peasant weddings virtually everywhere in East Central Europe lasted two to seven days and were replete with some of the oldest rituals, songs, dances, and instrumental music among rural populations. Today, peasant wedding rituals and music practices in most locales are rare or even defunct, while in several exceptional regions they continue to be practiced.

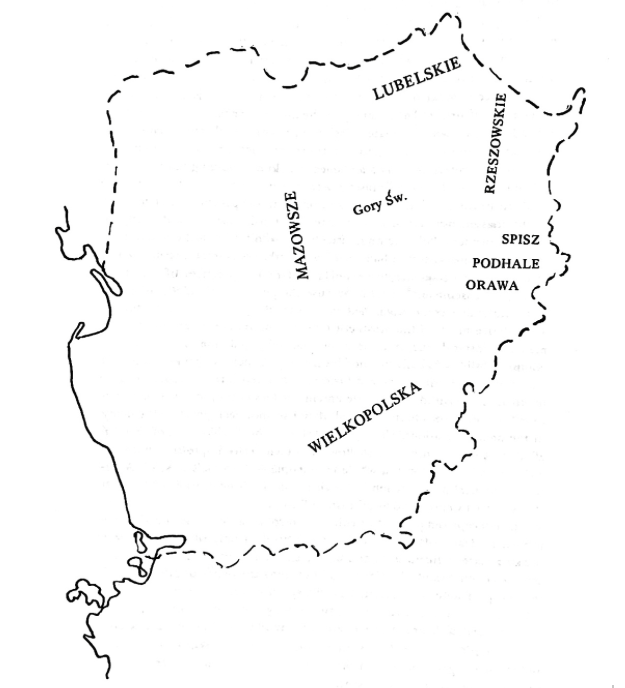

In Polish lands, the decline in some regions began as early as the first decade of the nineteenth cnetury, notably in locales in Wielkopolska, what is today western Poland. In other regions, the decline began in the second half of the nineteenth century as urban fashion was increasingly adopted by ever larger numbers of villagers, as in regions near the then industrializing and growing urban centers Łódź and Warsaw. Peasant wedding practices had declined considerably in most regions by the 1920’s-30’s. Today, for the most part, only fragments of the ancient peasant ritual wedding remain in certain regions, and then often only in a few villages. In most locales, little remains of older peasant wedding practices and urban-derived practices dominate. There are regional exceptions where older peasant wedding and music practices prevail, or at least are still important in village life, usually with additions to and deletions from the nineteenth century practices; e.g. the highland region Podhale and to a certain extent Spisz and Orawa; in scattered locales in the foothills regions of the Tatra and Bieszczady mountain ranges; in scattered locales in Rzeszowskie and greater Lubelskie (including Zamojskie); in a few locales in Mazowsze and the Góry Świętokrzyski; and in several locales in greater Wielkopolska, particularly in the region Ziemia Lubuska (see map).

In the past, when the peasant wedding sequence was a vital part of village life in virtually all regions, certain of the guests at a peasant wedding assumed specific roles. These roles demanded the ritual execution of specific texts, melodies, orations, incantations, monetary payments, dances, processions, food preparations, alcohol consumption, feasting, etc. As noted by the early twentieth century Polish ethnographer and historian Jan S. Bystron:

A [peasant] wedding is something on the order of grand opera, lasting several days; the actors of that great spectacle have a specifically assigned role and in the prescribed moments [utilize musical events] that carry out the action of the ritual.

The “actors” were ritualized characters. Each character was assumed and the role was acted out in ways prescribed, at least in part, by local custom. Within this series of ritual events, the characters performed a number of duties. For example, one character danced with another at a specific point in the sequence, or a certain character sang a specific melody at another point in the sequence, or the music ensemble rendered a specific genre at a certain point in the sequence.

Among the most important of the characters were: the bridge and groom; the go-between or matchmakers; older guides to rituals and order who served as master-of-ceremonies or sergeant-at-arms; bridesmaids and groomsmen and older figures of authority from their ranks. Other villagers who figured prominently in the wedding sequence but who did not assume a specific character role included: the priest, the innkeeper, the local nobleman, and the village musicians. The priest’s role was primarily at the exchange of religious wedding vows in church. The innkeeper was important because before the 1880’s or so, much of the peasant wedding sequence in many regions was realized in the local inn. The peasant huts were often too small and too full of smoke (homes without chimneys were common then) to accommodate crowds. Up to peasant enfranchisement in the mid-nineteeth century, the nobleman was consulted by the bride’s and groom’s families and at least one wedding event took place near the manor house. Village musicians played a pivotal role in a large number of the wedding events, some of which are discussed below. Although the sequence of events in a peasant wedding is too long, complex and regionally diverse to be discussed in detail here, a few general comments help to illustrate the importance of the village muzykant and his ensemble music in many of these wedding events.

Instrumental Music in the Wedding Sequence

In certain but not all regions, a fiddle player was present at the negotiations between families for future spouses of the young adults. After the wedding agreements were made, the family members and the go-between, matchmaker or other family representatives downed a toast to the accompaniment of the fiddle player’s music. Later, approximately two weeks before the exchange of wedding vows in church, the invitations to the wesele were extended by each family to those who were to be guests. In many locales, this was done by specific wedding characters who walked through the village and at each prospective guest’s home, orally issued a ritual invitation. In some regions, an ensemble or a single musician (usually a fiddler) accompanied these rounds and realized specific melodies at each hut in turn.

On the evening before the exchange of religious wedding vows in church, in most locales there were social gatherings (wieczorniki) of family and close friends either at the village inn, or at the groom’s and/or the bride’s homes. Village musicians were usually engaged and played until late into the night, providing both dance music and accompaniment to certain wedding songs.

Throughout the twenty-four hours of the day of the exchange of religious wedding vows in church, the peasant music ensemble was vital to several events, and in some regions played almost nonstop from early morning until late at night, even through the night and into the next day. In the early morning of that day, all the groom’s guests gathered at his home, and the bride’s guests at her home. Ritual melodies were realized by the peasant instrumental ensemble, including “greeting pieces” as each guest was met in turn at the door by the ensemble playing a locally specified greeting melody, in the second half of the nineteenth century in many regions, often a march. By mid-morning, the groom and his retinue of family and guests set off for the bride’s home to the accompaniment of the instrumental ensemble. The repertory for this event was the drogowe (“on-the-road”) tunes, often heard only in this or a similar processional context. Upon arrival, a series of musical and ritual events occurred, many involving ritual texts that were, in some regions, accompanied by the ensemble, including: the parents’ blessings (błogosławieństwo), ritual banter between the leaders of the families, the blessing of the ceremonial bread and other wedding objects; also occurring at this time were more ritual greeting tunes, rendered by the ensemble in honor of each guest, one at a time. Local and regional customs varied in all of these. After food, drink and other ritual events, the entire wedding procession set off for the church. The procession could move only in a prescribed order which varied from village to village. In one village (Albigowa) in the region Rzeszowskie, the order circa 1920 was: the bride in front and flanked by two elder bridesmaids; followed by the groom who was flanked by two elder groomsmen; followed by the peasant music ensemble; followed by the parents of both families; followed by other important wedding characters; followed by the wedding guests.

The trip back from the church after the religious wedding ceremony usually was in the same order. The destination of the procession at this point in the ritual sequence varied greatly by region and time period. In some cases the procession went back to the bride’s home, in other cases to the village inn, or in still others to the nobleman’s manor. In each scene, regional music and dance as well as feasting and drinking were featured. In the late nineteenth century in some locales, as part of the effort by members of the clergy to encourage sobriety among the local population, the procession went from the church to the priest’s residence, where no drinking was allowed, and where the celebrations took place in the priest’s yard, including music and dancing.

From this point in the sequence of wedding events, the specifics become even more regionally diverse and therefore difficult to discuss without detailed reference to the enormous body of ethnographic study in several Central and East European languages. In brief it can be said that the new couple was honored in various ways, including through ritual dance and music. Some of the dance and music genres were known only locally, others were regionally dispersed. Still others were known over a wide area, much of Central and Eastern Europe, or even continentally.