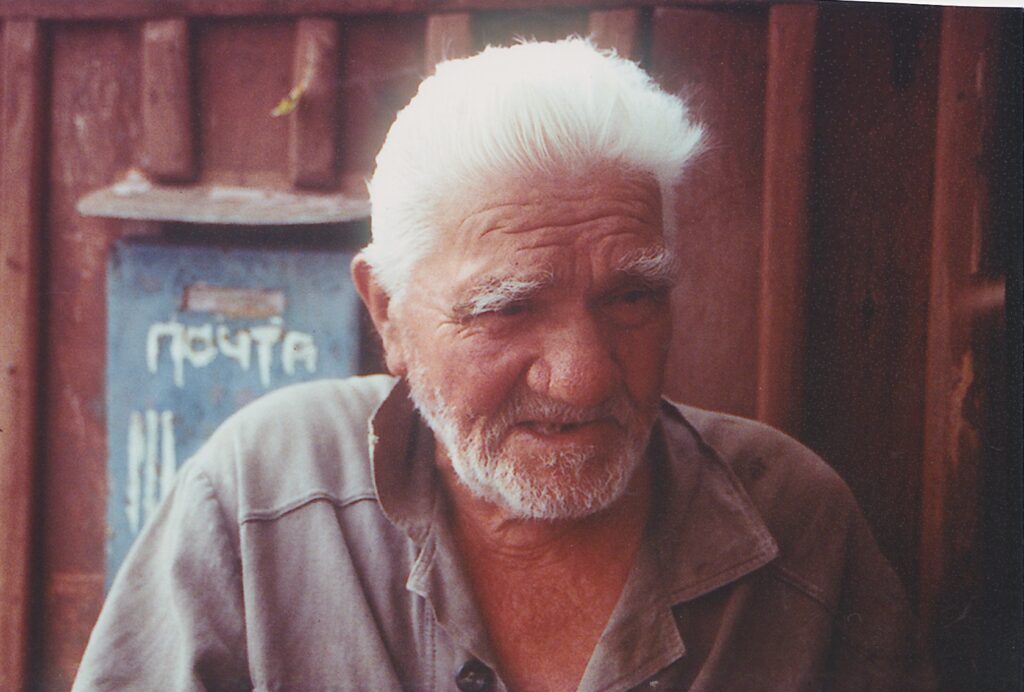

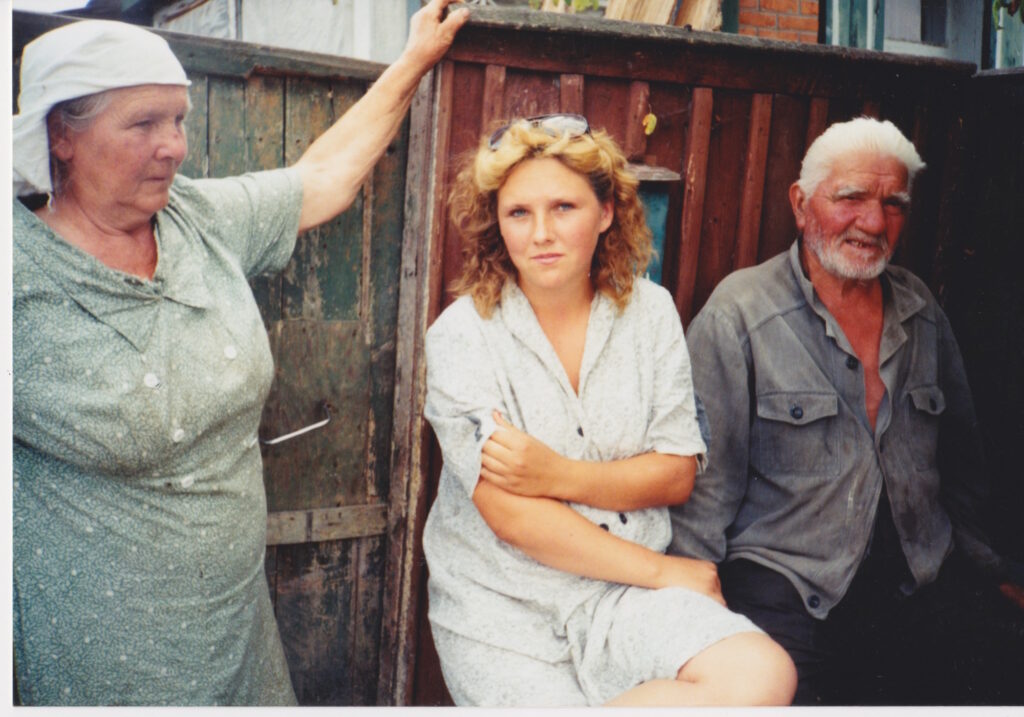

Nadezha Mykyta Mykolaiovych, b.1097 and his wife Nadezha Teklia Ivanivna

—When were you born?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 1907.

—In what village were you born?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Stara Hlynytsia of the Chuhuivs’kiy district.

—Was your family Ukrainian or Russian?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Ukrainian.

—Did your parents speak Ukrainian?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes.

—How many children did they have?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Eight.

—How much land did the own?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They didn’t have any.

—Were they serfs?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They were serfs during serfdom. The landowners gave land, and the people worked for them. We were born after the landowners had divided the land. This is how our whole village ended up without the land. So, they live without any land. There are the kolhospy now. We didn’t have any land and worked [for a landowner]. The landowner was a German named Weiss Retermurt.

—Where was his homestead? In which village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Oh, he had divisions in Stara Hlynytsia, Bilokolodiaz’, and Zmiiov. He grew sugar beets. My father worked for him. There were our local landowners and 1,500 hectares of land. My father worked for the landowner as a milkman for 15 years. He preferred only men as milkmen. His lady was in charge of the administration and kept the ledger of how much milk each cow produced. Only men milked the cows; she didn’t like women. She would sit on the chair and make notes.

—What was the name of that landowner for whom your father was a milkman?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Iefremenko, Iakhmovs’kyi, Iakhno. The priest in our village was named Iakhno and the landowner was Iakhno.

—Why did you say Iefremenko?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: His first name was Iefremenko, and his last name was Iakhno.

—Did he just live there?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, no. He bought land. He was not a Ukrainian. He was a Latvian or something… He bought land here. We had three widow sisters there whose father was a duke [kniaz’]. I don’t know how this came about. When their father died, they sold that land and left. I don’t know where they went. And so, he was a landowner there until the Revolution.

—What happened to him after?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He left in 1918. The Revolution. They all left.

—Before the Revolution, when your father worked for the landowner, were those landowners kind to people?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: How shall I put it—so-so. This is how it was and still is: if you’re a good worker, the landowner or the khaziaiin is kind to you. This is how it was back then and still is. A good worker was appreciated and spared. Some would give their people two liters of milk every morning. Each worker had a two-liter bottle. A woman would bring out the container — “That’s your milk.”— and the men would pour it into their bottles. There were some landowners who would beat their workers a great deal. Some had to be loved, and some — beaten.

—How much was your father paid by the landlord?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 7.5 rubli per month. Life was hard.

—What did your mother do?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: She was a housewife with eight children.

—What did your father do after 1917?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We got the land, and a good life began for us. Lenin gave land; we got 18 hectares; at the time, land was measured in desiatyny. A hectare was less than a desiatyna [a desiatyna is 1.09 hectares]. A German plowed our land. There was also a law (serfdom): land was allotted to men only, not women. We divided the land between all at the time of the Soviet regime in 1917. A child would be born in the village—by then, there were no midwives left (we called them baba in the village)—and someone would run to announce it: “Guys, come, a baby was born.” But who knew that it was born? “So, guys, are we allotting land to the newborn?” — “Sure thing.” As soon as they gave land to that man, comes another one: “I have twins. Baba Habylykha was the midwife.” Habylykha was a well-known midwife in the village.

—Was Habylykha her name?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes.

—Who divided the land?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The village men.

—Was there no one in charge?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No. They would choose an elder and divide the land on their own. All on their own.

—How did they go about choosing the elder?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: How? Soviet power. Usually, they would choose among the decent men. The officers were not allowed at the time, but we had two that were elected. They went through the regiment school and headed the Soviet authorities.

—When people were dividing the land, did everyone get an equal plot?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, an equal plot per person.

—How much land was given per person?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 1.5 desiatyny.

—Did your father have a garden after 1917?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes. He also had the land and the farmstead. He had everything: a cow, a horse, everything.

—Where did he get the money at the time?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He sold the grain to the cooperative. This was the same farm as we have now. And it’s the same process now. Some grow crops, and some do something else. Some bring the grain, and others—something else.

—Did your father grow crops only or did he do something else in addition?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He only grew crops. Nothing else.

—Did he take anything to sell on the market?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes.

—Where did he go to the market?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Chuhuiv.

—Did you go with him, too?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I was as little at the time as my grandson is now. Yes, I used to go with my father. The money had high value at the time, and there were many goods.

—Was there a tavern [shynok] in the village before the revolution?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was a tavern.

—Where was it located?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In the old house.

—Who was its owner?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: A crook who ripped people off. He was clever and knew where to make easy money. My father was not smart that way. He was just a milkman, what did he know? And I finished three years of school.

—Where did you go to school?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In my village.

—Was this a church school?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, of course. There were church lessons and a priest. Why did the priest beat me? It was around 1917, the Revolution was coming up; my uncles and brothers worked for Retermurt Weiss. On the weekend, they would come to the house and play cards and drink. There was an icon in the house: Peter the Great was on top of a white horse holding a spear. A snake coiled itself around the horse, and Peter the Great was fighting the snake with a spear. My uncle said, “What kind of a God is this? A snake attacked him, and he’s hitting it with a spear. Can this be God?” I heard this and retold this to the guys at school. Then the priest came to the lesson, and someone said, “Father, Nadezha committed blasphemy.” — “How? Come here, Nadezha, and explain how you committed blasphemy.” — “I didn’t.” — “He said, is it God depicted as Peter the Great on a horse, hitting a snake with a spear?” This was in 1914. When the priest was on this way to a lesson, the guys that were on duty would come running: “Nadezha, go stand in the corner.” So, I spent all his lessons standing in the corner.

—Who owned the tavern?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: A peasant. He had a store, so he would buy produce, and the people would party and drink. A bottle of vodka cost 40 kopiiky in the store, and he sold one for 42 kopiiky.

—Did only men drink there or women, too?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Both men and women drank and partied. They didn’t want to work.

—Did musicians sometimes play in the tavern?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, there was music. They would put a gramophone in the window, and you could hear it across the whole village.

—Did any musicians play there?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No.

—When you were a schoolboy, what language was used to teach in school?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Mostly Ukrainian.

—What language did the priest use?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He knew several languages. We were taught some Old Slavonic and Russian, but mostly Ukrainian.

—When you started socializing as a young man, how did you join the group of guys?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: After the Revolution. After 1917. The group was organized right away. I had linen pants, not bleached or anything. I wore them just like they were made and I used a peasant bag to go to school. We made all the clothes by ourselves. My mother would cut half a cloth and stitch a rope in and I would put the primer into the bag.

—Did you have any books?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Sure I did.

—Were there any newspapers in the village at the time?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, nothing.

—How many years of schooling did you have?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Three. There were only three years of schooling everywhere in the village before the Revolution of 1917. After 1917, larger villages had 10-year schools. A small village like ours would have five or seven classes.

—How many houses were in your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 400.

—Was it a large village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, medium-sized.

—How old were you when you started going out with the girls and the guys?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Around 16.

—When you first went out, did the guys bully you or make you do something?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, I began my cultural life after 1917. It was a totally different life. We didn’t have a moment to breathe at the time. There was no culture; after 1917, they set up a reading house and showed some films—not often, about twice a month. We started getting people together; we started getting magazines in the reading house. Vechornytsi stopped; the reading house had newspapers and one pair of headphones. Then they started buying more, organizing the hobby groups, and staging plays and concerts.

—What plays were staged?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Plays about the bandura and the Cossacks. The first play was Natalka Poltavka. Then the hobby groups were organized, and the church was destroyed. Before, people used to sing in the church; when it was destroyed, the singers came to the club. In our village, we called it the reading house, not the club.

—Did they sing religious songs?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, no. They sang old Ukrainian songs.

—Did they sing songs about Lenin?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Of course, about his childhood, his life, and the life he made for others. I will tell you this directly: Soviet power provided for us and should continue to provide us now. We need to bring Soviet power back so that the average man can be in charge.

—When did the power belong to the people?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In 1917 when the Soviet authorities gave it to us. Lenin gave us land and the right to choose the authorities.

—When the kolhospy began, was the land taken away? Were those the Soviet authorities or not?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The Soviets. No one took the land. Who told you that land was taken away? We have the decree confirming the indefinite use of the land.

—Do you have this decree?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We have it in the [kolhsop] office. It says in gilded letters that the land in the kolhosp is ours for indefinite use. It’s a large book and in gilded letters it says: the land is transferred to the kolhosp workers for indefinite use.

—After 1917, did life change for the better?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: It became totally better.

—Did you go to vechornytsi?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Of course. It was a good time. When it was over, when the Soviet regime began…

—Where did you gather for vechornytsi? What house did you rent?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Girls used to gather (about five or six of them); they would choose a house and arrange with the man or woman who owned the house about how they would pay for it.

—How did they pay for it?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In various ways. Some could whitewash the walls or bring the firewood, clean or bring some pirozhky (“stuffed pastries”). They made the arrangements. The rich ones wouldn’t let them in, but the poor ones or the widows would let them come. When such a woman let the girls in, it was more fun for her and they would bring the firewood and the food.

—Would the girls go to her house throughout the whole winter?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, the whole winter.

—What about the guys?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Guys would come. The girls would be spinning yarn until Friday, and on Friday—God forbid; you could only sew. Such was God’s law. On Friday, you could only sew, not spin yarn. On Saturday, you would whitewash the house and do laundry.

—When the guys came over, what did they do?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They would sit around, sing, and eat [probably sunflower or pumpkin] seeds.

—Did they play cards?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No.

—Did the girls sometimes go to another village neighborhood for vechornytsi?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Our village wasn’t very big, about 400 houses. There were about 10 houses where vechornytsi were held. Most people went to party in their kutok because the village was spread out. Not everyone wanted to go to the other side of the village. They mostly gathered here, locally.

—Did the guys come to meet with the same girls all the time?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No. It was allowed [for the guys] to go to various neighborhoods.

—What about the girls?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Same goes for girls. Those who lived on one street gathered in that street, and those who lived on the other street would party in that street.

—Could the girls from one street go to the other street?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They could, but it was rare. It was allowed and some used to go, but rarely; maybe this was not convenient.

—Did the guys sometimes hire musicians?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, there were the musicians. Harmonia, mostly.

—Did they hire an older man to play or was the musician young?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: A guy the same age as everyone else. If one harmonia player got married, he was no longer available, so someone younger would come to replace him.

—When that harmonia player played, did everyone dance?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: People danced.

—What dances did they dance at the vechornytsi?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Oh! Mostly polka and hopak.

—Was there music in the reading house [khata-chytal’nia]?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, they started buying music. During the Soviet regime, the vechornytsi stopped, and the reading house took over.

—Did all the girls who used to go to the vechornytsi go to the club?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Girls used to come, too.

—Could they spin yarn there?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The cultural activities at the reading house were more developed at the time. The church stopped working, and the people who sang in the church got together in the club, too. The church starosta chose the singers for the choir. Now, the church choir sings better; they are all well chosen. The church was closed down once it was acknowledged that it was not necessary. Indeed, it wasn’t necessary, not for me.

—Did you not wed in church?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, I hate them all.

—What year did you get married?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: After the war.

—What did people do in the reading house?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There were concerts and theater plays. People read there, too.

—Who was in charge?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The komsomol’ members. The military chiefs would come; the plays were staged often. The Soviet government gave us a totally different life.

—You said there were plays about the bandura?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Bandura players. Taras Shevchenko played the bandura, so people called him a bandura player. That was about him.

—When was the kolhosp starting to be set up in your village? Was there a SOZ before the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was a SOZ first.

—In what year?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 1928.

—Who started the kolhosp in your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The paupers. SOZ were the paupers. I joined a SOZ when I was 16. Our family gave up their land (they were well-off), and the pauper who got the land had eight people in the family—1.5 desiatyny per person, so he got a total of 12 desiatyny.

—Was it much?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Not much, but they had no tools to work the land. They elected a man and a woman as representatives to send to Lenin so he would give us, the poor, a tractor. Komnezam organized this, and Lenin approved. He signed a document for the Kharkiv region, and we got a tractor. My uncle was the chairman of the Committee of the Poor Peasants and he organized all this. He sent me to Kharkiv for a month to learn how to work the tractor while they were waiting for me here. They gave me a tractor there. I was on my way from Kharkiv but made it to Chuhuiv; the tractor broke down on the way because I was a fool and didn’t check it. That tractor fell apart and burned down. I got up, left the tractor there, and walked barefoot to Kharkiv. “What happened?” I told them the story. They gave me another tractor and a mechanic. He and I went to my village; he fixed the tractor and showed me everything. I was there for a month, and he showed me everything. Then I drove that tractor.

—What organization was this?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: “Sil’khozsnab” [“Agricultural Supply”].

—What kind of work did you do with the tractor?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Well, we had this SOZ. Komnezam gave us good land.

—Your father owned land, so he didn’t join?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, he didn’t join.

—How many of you were in this SOZ?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: About 15.

—They also came without the land of their own?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, without the land.

—Where did you get better land from?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We had a society with some extra land. You understand, a newcomer would move in with his family to live here, so we should give him some land. This was how the society worked. Land had to be available for the people. The people would come—refugees, the Poles; they would get some land.

—You were 15 people in a SOZ, and how much land did you have?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 1.5 hectares per person.

—Was the land collective?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes. I plowed the land using the tractor; then we’d reap the harvest. We would then divide the harvest equally between all. The horses, the cows, and the tractor were all collective property. This was collective agriculture [SOZ].

—Where did you live?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Over there.

—Not at your father’s?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No.

—Did you build a house of your own?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, I lived at my father’s [??].

—You didn’t build a communal house?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No-no, we didn’t have this.

—Why didn’t SOZ last? Why did the kolhsop begin?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We went from SOZ to the kolhosp because we learned that SOZ was a middle-class farming enterprise, and the kolhosp was supporting the older people. We started setting up collective meals and helping the elderly. The cooperative was another stage. In the SOZ we would divide everything earned throughout the year. In the cooperative we had the poor members and the elderly, and the cooperative would help them. This was a different stage.

—When did the kolhsop begin?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In 1933. Stalin had vertigo in 1933, so he ordered collectivization. He was set up, and as strong as he was, he wasn’t afraid to accept the responsibility. Stalin had vertigo with this collective agriculture. This collectivization amounted to nothing. Like Horbachiov and his perestroika. So, Stalin said, “Dismiss the kolhospy.”

—So, the kolhospy began in 1931. What was the name of your uncle who was in charge of the SOZ?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Pavlo Nadezha.

—Did he become the head of the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, the other man did.

—Why?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: My uncle was the chairman of the Komnezam, and we had an organizer from Kharkiv, a stotysiachnyk (“hundred-thousander”). At the time, there were stotysiachnyky, young guys who were sent to the kolhosphy, the komsomol’ members. Pohorielov came to our village from Kursk and lived here.

—When the kolhosp was being set up, was Pohorielov in charge of it?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He was not in charge; he led it forward. There was no technology at the time, just the horses.

—You were 15 people in a SOZ? How did you tell others to join the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The people came on their own. They saw that life was good, came, and enrolled in the kolhosp. They were accepted.

—What about the rich?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: The kurkuli didn’t want to join the kolhosp. They were taxed, asked, and persuaded. They were taxed. Their land was not confiscated, but they were heavily taxed until they would pay, and they would pay until they had nothing left. Then the person would come, “Enroll me in the kolhosp.” This was how it was. Smarter people sold their farmsteads and left. Most of them fled to the sovkhozy. They were accepted to the sovkhozy, and life in the sovkhozy was better than in the kolhospy. They paid some money there and provided three meals per day; in the kolhsopy they only marked the days worked, and they gave everything except the money (there was no money). They paid money only at the end of the year.

—What did you do in the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I worked on the German tractor “Fordson” since 1928. The father’s name was “Ford” and so the son’s name was “Fordson”.

—Tell us about collectivization. Your wife says the land was confiscated, and you say it wasn’t?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No one confiscated anything. We came to the kolhosp and were given the book. There was a large meeting of all the kolhosp workers, and in gilded letters it said: the land is transferred to the kolhosp workers for indefinite use. The land was marked with pegs so no one used the other people’s land.

—Who gave this book to the kolhosp workers?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Sovnarkom.

—Why do other people say that they were forced to join the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I know this activism.

—Was it a lie?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: This was the same as this perestroika. Some people like it, and some don’t. Those who give bribes, the profiteers, and the hooligans like perestroika. It was the same at the time of collectivization. Lenin’s law was very good: work and earn. It was very good in the kolhosp.

—If the well-off people had the land and the cattle, why would they join the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Let them do their own work, but let them pay the taxes. But the taxes were set up in a way to make the rich join the kolhosp because otherwise they got in our way.

—How?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Because he would live better than we did. We had to work, and what about him? He would lie in the shade; he’d finish working his land and sit down to rest.

—How could he live better if he were resting in the shade so much?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Because we gave him a separate piece of land. Between the stretches of our land is a stretch of his; he would work a little on it, and leave to take a break.

Teklia Ivanivna: Don’t say this. Say that most people in the kolhosp were lazy, that’s all. Ivan’s father used to go fishing and would come to the kolhosp to get bread. They were all like this everywhere.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I know what you want to say. The journalists are waiting to see if the land can be split between the peasants. Nothing will come of out it. If you give them land, it’ll all be covered in weeds and people will die like flies.

—Teklia Ivanivna, if the land can be distributed again between the people, will they take care of it?

Teklia Ivanivna: No one will take it. In our village, only one man took the land. No one else did.

—How much land did he take?

Teklia Ivanivna: Around four hectares.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He doesn’t pay anything; no use to the government.

—Is he earning anything from the land?

Teklia Ivanivna: I guess so.

—Why doesn’t the state want to tax him?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: It will take him time to make profit. He was dragged into this the same way people were dragged into the kolhospy.

—You say that people were not forced to join the kolhosp but joined out of their own will?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They did (laughs).

—What were you saying about Stalin’s vertigo?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was a law for Sovnarkom: collective agriculture had to be set up on voluntary basis as in the example of our SOZ: we were 15 people who came together on a voluntary basis; we received a tractor; we asked for the land from the society; we got the land and worked. Some people did not accept this, so the authorities forced them to join the kolhosp. If they followed Lenin’s way (as he said—on a voluntary basis), the peasants could organize villages on their own. Stalin made the wrong decisions; he crushed Lenin’s policy completely.

—Did people in 1933 understand this and think the same way you think today?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I think they did not understand this. The Soviet government could not provide for the people, you understand? It could not provide neither bread, nor anything else. How could it? It had just begun; it was new and had to support an army in some way.

—Your neighbor said that people’s property was taken away and sold along the road?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No one took anything away except in the case of the rich individuals who didn’t share bread and used to hide it. They were taxed, but they didn’t pay the taxes.

—Was the grain that was confiscated from the people brought to the barn?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: To the barn first and then it was given to the government and the regional administrative center. No one sold a single grain anywhere else. This was all done by the party and the Soviet authorities; they had to feed the army and the people, and the rich were hiding the grain.

—Did everyone in the village understand what had to be paid back to the state?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Look, the renters now are using the land for the fourth year and have not paid a gram of produce [in tax].

—Where would a renter go if they don’t give him a shipping order?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He is subsidized and supported, but will his work have a good outcome or will he sell it back to the state? Now they give kolhospy and sovhospy to the state; there’s a decree, but this one sticks to his land. He has to give 30% to the state from his income.

—What exactly does he do?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He raises cattle and sells 30 kg of meat.

—Perhaps the state wants to create more of such producers and doesn’t want to tax them for now?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They won’t succeed. The only way to go about this is to keep the kolhospy and sovhospy. In the current situation, a single state cannot come out of the crisis on its own. It’s a struggle now for Belarus and Russia and the majority [of the post-Soviet republics] to have trade contacts; you can’t do without this and you can’t do it without collective farming. You have to turn back, only turn it back to collective farming on voluntary basis.

—The Lenin way?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Not the Stalin way, but the Lenin way.

Teklia Ivanivna: And to destroy all those communists. What use are they?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: If it’s the Lenin way, the communists are few.

—How can one tell the Lenin communists from the Stalin communists?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Walk around the village and you’ll know.

—What if they are not communists, but from Western Ukraine?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: What about it? I know what Western Ukraine wants. It wants to be independent and not give anyone anything; it wants to live independently and not let even the rest of Ukraine get involved and to make sure no Russian ever crosses its threshold.

—Ukraine is independent now. So, the Constitution says.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Is it really independent? It’s written in the Constitution; anyone can write anything. What good is it if it’s not working out?

—How many komsomol’tsi were there in your village in 1931?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: About 60 people.

—What about communists?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Few. About 10–15.

—Were you a komsomolets’ or a communist?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, I wasn’t.

—Why?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I didn’t belong to anything and didn’t have religion until I understood better and got some culture. Before I didn’t acknowledge any of this.

—And you didn’t want to join komsomol?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No.

—You didn’t want to join or did you have to fulfill some prerequisite to join?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, they didn’t accept me, I didn’t want to join, I didn’t have time. You had to sit in the reading house in komsomol, listen to something, put on these headphones, know that tomorrow they would ratify the decree about Taras Bulba, about the peasants, about Natalka Poltavka, all that. I didn’t have the time. I got that tractor in 1928 and was underneath it, fixing it, all covered in oil, barefoot.

—And you didn’t get married?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: What kind of a groom would I make? Barefoot, dirty, my hat full of holes—a tramp. When we joined [object of the verb is unclear] and I had to have a different life, but I had no time.

—Was there a famine in your kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Famine? I don’t know. This is a political affair.

—How many people died?

Tekllia Ivanivna: Not quite everyone.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was a famine in Ukraine.

—And in your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was a famine here, too. I was a tractor driver. People died like flies. Someone would go into a thicket to find the last year’s potato or some herbs and would die right there. We used to plow last year’s thickets and we would sometimes plow through the dead bodies there. What could one do with them? No one could bury them properly because all the living ones were swollen and weak. This is a political affair; you must know better that this is what Stalin did.

—Auntie, did you see any cases of cannibalism?

Teklia Ivanivna: One woman here told me about a woman who lived alone about 10 houses away. If a child came to her house, it didn’t come back; comes in, but doesn’t come out, comes in, but doesn’t come out. This woman said she came to her house one time, and she said, “Lenochka, in the oven there are two pots with meat. Pass me one.” She said, “I poured her some, and she ate it.” Then she said, “Give me some more.” She poured some more and saw children’s hands. She said that she rushed out of the house. That woman [the cannibal] died and the meat stayed in the oven. When she died, they found a lot of human bones on the ledges [of the stove] in the house.

—Would it happen in your village that a mother of a large family would leave her child at the train station?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Some did.

—Why?

Teklia Ivanivna: They thought the government would pick the child up and maybe the child would survive. At home, the child would have died.

—What did the people think was the cause of the famine?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They thought it was due to the atmospheric causes; there was a propaganda campaign saying that this was the year of a poor harvest and the drought, so there was no bread. Then the people understood that it happened only in Ukraine. Not everyone understood the real cause; some did, but you could not say it directly. You know how Stalin ruled. The people knew who did this; the politicians and the party members knew. We had the Communists in the village, but who could openly tell me that it was wrong? They kept sending the message that it was due to a bad harvest and a drought in Ukraine, and things were different in Russia. Why was it different in Russia if they also had the Soviet regime there? Later on, you could talk openly about this. This was a political affair. This is a very difficult question.

—After the famine, did the people come to enlist in the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Some did.

—Someone said the famine aimed to make all the people join the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, that’s not the reason. This was Stalin’s work. He destroyed many Bolsheviks: Kirov, Postyshev. He killed them. Perhaps this was done with a similar purpose—to exterminate the people so they would not start a revolution, something like this. This is a political case and very hard to crack. No one has solved it to this day. I am being honest with you.

—How did you manage to work at the time? One has to eat to have the energy to work, and there was no food at the time. Was there a working kitchen in the kolhosp at the time?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, they prepared food and gave it out little by little. Our chiefs were from Kubins’kyi regiment. They were stationed in Chuhuiv and they gave us (especially the mechanics) grain and bread. There was a time when we had seven tractors and I was the brigade chief, and the chiefs helped the people; they brought the corncobs without the grains, just the cobs, to the mill. People would boil these cobs in a large pot. It was a very difficult time. Why it happened, I cannot say. Now no one can prove why exactly Stalin did this; he killed the Bolsheviks so they would not replace him; you can see the famine in a similar way. He decreased the population in the nation so people would live in fear. You could understand it this way, but no one knew for sure.

—Tell us about your marriage.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I don’t know how we got married; that was her work… She was young, and I am old, you see. She is 16 years younger than me. She was left alone without her mother or her father, and I was a tractor driver, a brigade leader, then I was the mechanic at the machine tractor station, a hero. They were chasing after me.

—Did you have a house at the time?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: So, she came up to me and said, “I guess I will live with you.”

Teklia Ivanivna: Yeah, right.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Well, you tell them then. How was it?

Teklia Ivanivna: We got married, that was all.

—Which of you had a house?

Teklia Ivanivna: Neither of us had anything.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We rented an apartment.

—Did you come to propose?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: There was no such thing. It was after the war.

Teklia Ivanivna: People do the matchmaking and proposals now, but after the war, you know how we lived. We had nothing. Now we have a granddaughter.

—How was the church closed down in your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I remember this. It was closed down, the priest was expelled, and his house was confiscated.

—What was the house used for?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Village council. The priest was resettled. Each church had a lodge [a small storage space, a shed] where possessional materials were kept and where the custodian lived. They resettled the priest into that lodge.

—Did he have a family?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, a mother and a daughter. He died in 1933; life was hard. The old women would bring him food.

—When was the church closed down?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: 1933.

—What was done to the building?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: It was dismantled, pulled apart. The cross was thrown off; the metal and the bells were collected and sent to Kharkiv. The icons were looted. Some women who understood theology took them. There used to be old people who knew theology.

—Who was in charge of this?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Komnezam [Committee of Poor Peasants].

—Was your uncle the head of Komnezam?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: My uncle and the poor peasants.

—Did he worry afterwards that this [destroying the church] was a sin?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Why would he worry? He lived very well.

—Did you help them a little?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Me? I didn’t know about this at the time. When I was given a tractor in 1928, I never left it. I went from the SOZ to the guild, and from the guild to the machine tractor station.

Teklia Ivanivna: When he joined the machine tractor station, he had nothing to do with the kolhosp anymore.

—What did your uncle do in the kolhosp?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He was a komnezam, the committee of poor peasants.

—What did that committee do?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Nothing. The poor people got together and received good land; I used to plow the land for them with the tractor. Whatever I earned, we used to party and drink. We split the harvest between us.

—Where did you buy vodka?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In the store.

—Where was the reading house set up?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In the former priest’s house. He had a good one. He was evicted.

—Were the village council and the reading house in the same building?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, the priest had six rooms in his house.

—Was the reading house established before the village council?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes. A man was dispossessed and evicted, and his house was confiscated and used for the reading house. Then they took the priest’s house which had six rooms, and both the village council and the reading house moved there.

—What year was the first reading house set up?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Approximately 1928.

—Not earlier in 1921, 1922?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, no.

—When the kolhosp was set up, did the girls still go to the vechornytsi or was it forbidden?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No, the vechornytsi stopped on their own. The reading house took over; they stopped spinning yarn and sewing.

—They could rest in the reading house but had to work during the vechornytsi, right?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They were spinning yarn there, but this stopped on its own.

—Were there any icon painters in the village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No.

—Where did people buy icons before collectivization?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: In specialized stores in Chuhuiv. At the time, people had to give the bride and the groom icons for the wedding. It was mandatory. There were specialized stores that sold icons. With the Soviet government, the icons disappeared.

—What was the music like at the weddings before the Revolution?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Harmonia and bubon.

—Were there any fiddles?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No. We had two musicians: she played the bubon, and he played the harmonia. They would get hired for weddings, play for three days, and be treated to a drink there.

—Did they pay them anything?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes. If there were any pastries left, they would take some.

—Were they husband and wife?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes.

—When you were little, did the blind startsi come to your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, they were not startsi but narodnyky.

—Who are the narodnyky?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Startsi were the ones who asked for alms if there was some kind of a misfortune, for example, if their house had burned down. These people who went around asking for alms that people called startsi are actually narodnyky.

—What would a narodnyk say when he came to someone’s house?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: He would talk about his difficult life. We had one in our village; his name was Fed’ko Burta; he was very poor and his house was all overgrown with weeds. He used to go around asking for alms. Once a year, he would come to his house where he had some hay on the floor. Back then, the newspaper Iskra came out; the church did it [sic], the priests did it [sic], the administrator did it [sic], and there was also the police. The neighbors would say, “Fed’ka came.” They would run to him and he would read the newspaper.

—When did the newspaper come out? In 1905?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Oh, right, in 1905. So, he would pull out the newspaper and read it. The old women would go to the priest, “Father, Fed’ka Burta came and pulled out the newspaper. He read that there would be no gods, no church.” The priest said, “Where’s that man Fed’ka?” — “He’s home.” Fed’ka was no fool; he took his bags in the morning and left. When the priest came, he was no longer there. The priest said, “Ladies, when he comes back, let me know.” Fed’ka came back in a year, and the ideas were different at the time; he gave out the brochures. The priest came with the police, “Stop!” And they took Fed’ka, and to this day he’s not been found. That was a narodnyk.

—Were there any blind people?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes. They would mostly take coins or pastries, but most people gave money because it was what people needed to live.

—Did people always give them something?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes, yes, people helped them—no question about it.

—What did they sing?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: “Our father who art in heaven” and the religious songs.

—Did they play any instruments?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They played the bandura.

—Did anyone in your village play the bandura?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: No one. The bandura players would come from other villages.

—Did you know the player that lived in your village?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: We are not local. We moved here in 1953.

Teklia Ivanivna: He was a brigade chief of a tractor brigade. He was assigned to this village.

—As a stotysiachnyk?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Mhm. I was conscripted. I didn’t think of returning to agriculture; I’ve had enough of it. I worked for two months at the factory, and then I was called to the Human Resources department: “Leave the workplace immediately and go.” — “Where to?” — “To the Human Resources department in Chuhuiv. They will tell you what’s next.”

—Why did you go to work at the factory in Kharkiv? Why did you leave the tractor?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I was sick and tired of agriculture. It was very difficult. So, I came to the Human Resources department, “Come. You are a machine operator. We have a decree to send all the machine operators, agriculturalists, specialists, and all agriculture worked to the cities.” So, we were all sent to different places, regardless of our desire. You had to go and work in agriculture. I was sent here, so I came here to suffer. This is shit, not a village. We had a good village. We had Retermurt’s land; it was good land. Even now, the land here is not that good, and life isn’t good here either. Over there, the land is better, and people are better off. If you offer people there some land for free, they won’t want it. They will say, “Just give me the kolhospy.” This is further away from Chuhuiv, on the other side of Kharkiv.

—Do those komsomoltsi still live there?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Yes.

—What are their names?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: I’ve forgotten. You can find them there. Their kolhsop is great! The land is very good there, not like here.

Teklia Ivanivna: In our village all the people are Ukrainians [in the interview, khokhly]. We also have Georgians, Jews [zhydy], Jews [ievreii], and Russians [not clear why she used two different words for Jews].

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Most of them are Jews [ievreii]. The locals are just about 100 people.

—Did they buy the country houses here?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They fled. You know why? When the atom was moved, America got more active.

—America got more active?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Didn’t you hear? What kind of a journalist are you? I guess you’re questioning me. You know everything.

—In the 1960s, did the Jews move here?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: They are running away from everywhere. They came here, and back in the day they were running away.

Teklia Ivanivna: You say Ukraine is independent. Is it really? Have you been to a market in Chuhuiv? Go take a look. How independent is it if there are so many Georgians on the market? They are selling lipstick, earrings, and all kinds of trifles, things to paint your eyes with. He’s sitting on the market there, and a Ukrainian is working in the field at home. If this were Ukraine, all the people would have been our people, Ukrainians. Go take a look at Chuhuiv. Kharkiv is the same way, even worse. One person in our village said, “I went to Lviv. People on the market there are selling only their local produce: milk, meat, cucumbers, and eggplant.” Go look at our market; they are selling vodka. Vodka costs 28 at the store, and the person on the market is asking 40. And no one says anything. So, people say: is it Ukraine? When Ukraine was under the damned Soviet government, nobody … that… at least, nobody sold that.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: You have to bring everything back to the cooperative organization. Whatever I acquired, give to the cooperative for the exchange.

—Could you buy anything you needed on the market during the Soviet times?

Teklia Ivanivna: On the markets they would sell only what we bought: eggplant, cabbage, and meat; there was nothing from the stores.

—Auntie, what is your name?

Teklia Ivanivna: Teklia Ivanivna Nadezhyna. My children’s last name is Nadezhyny, too.

—Why is your husband’s name Nadezha and yours Nadezhyna?

Teklia Ivanivna: This is how it was recorded when we registered our marriage.

—What is your maiden name?

Teklia Ivanivna: Velyka.

—And your mother’s?

Teklia Ivanivna: I don’t remember.

—You said in that village all the residents were Ukrainians. Who are the local residents here? I’m asking because that woman speaks Russian.

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: That woman is a native.

—But she speaks Russian. So does Hanna Illivna. Didn’t Ukrainians live here?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Piatnyts’ke was a Russian village.

—Why is it in Ukraine if it is Russian?

Teklia Ivanivna: You know, people used to say that there were prisoners here, convicts, and so they stayed on and the village was Russian.

—What would you like Ukraine to be?

Teklia Ivanivna: Independent. No profiteering. No Georgia, no Armenia. I want all of us here to be Ukrainians. Well, Russians are Russians, they are the same as Ukrainians. Take a look and see if a Georgian works anywhere. One of our neighbors has a son-in-law [from Georgia?]. He’s a profiteer. He buys cars in Poland and sells them here. Does he need to go to war there? His sister is here, and they don’t want to go there until the war ends.

—You said there used to be a club with film screenings in the village? Why is it gone?

Teklia Ivanivna: Because it’s just the hooligans now. No one goes to the club.

— What would Mykyta Mykolaiovych like Ukraine to be?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Friendly. To be friends not just with Russia, but with all the nations on the planet.

—Isn’t Ukraine friendly now?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: It is, as you said, independent. Let it be independent. Let it have its own religion, its language—please. Learn Russian, well, friendship, only friendship. Do not, under any circumstances, dismiss the sovkhozy or kolhospy; they need to be supported. The government supported them with technologies and money. They need to be supported with everything; workers and grain farmers need to be paid. This is the primary task. If the new President [1994] considers all this and pays attention to agriculture, the economy will grow. If he doesn’t, nothing will work. And friendship, only friendship. Let Ukraine stay independent. We can’t grow the economy without the friendship.

—Isn’t Ukraine friendly now?

Mykyta Mykolaiovych: Oh, this I don’t know when the new President comes. It will be hard, but we will survive. Look what progress the country has made. Who was the first man to go to space? People say Gagarin was the duke’s son. And who taught him?

Teklia Ivanivna: Enough talking. You don’t know these people. Maybe they came from America.